Before Home Video Part 1- The Richard J. Anobile Interview: Photonovels, Fankenstein, Alien, Groucho and me.

We live in a golden era for movie lovers; At any point, one can access a beloved movie by downloading it, streaming it, renting it or buying it. The entire History of cinema is literally at people’s fingertips. With a minimal amount of browsing either on your computer or on a television streaming service, literally thousands of movies can be accessed within minutes. And yet there are still moments when we’re going to complain ‘’there’s nothing good to watch’’.

But there

was a time when, not all that distant from now, if you wanted to experience a

movie you loved, there were no ways to see it at any moment like now. Not on

Youtube. Not as a torrent or on Netflix. Not a rental Blu-Ray or DVD. Not even

on VHS.

Before the

eighties, when home video took hold of pop culture and invaded our homes, there

were very few ways you could see your favourite film. Either you waited for it

to play on TV, truncated, reformatted, censored and interrupted by commercials.

Or you waited for it to pop up at a local second run cinema or a movie

festival.

As a young

movie lover in the seventies and early eighties, I had found a few ways to

experience a film in a different way. I would listen to records that would use

audio clips from the film to tell the story, with only the sleeve as a reminder

of the visuals of the film. I remember owning THE STORY OF STAR WARS and THE

STORY OF THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK, and lying down in bed with my eyes closed,

replaying the film in my mind’s eye.

I would get

out my cassette recorder and holding a microphone to the television, would record

the sound from the broadcast of films like JAWS or SUPERMAN: THE MOVIE in its

extended TV cut. I would later listen to those tapes in pretty much the same

fashion as I would listen to the STAR WARS LPs. I was surprised recently, while listening to the HOW IS THIS MOVIE Podcast,

to

hear that an accomplished director had done a rather creative version of

this. As a young movie fan, director Phil Joanou loved Spielberg’s JAWS so

much that he went to the theatre near the end of the run, photographed every

shot of the film, and using a cassette recorder, recorded the sound of the

film. He went home, printed out 4X6 of those photos, pinned them in sequence on

his closet doors, and would play the tape while looking at the photos to relive

the film.

Being a

science-fiction fan, I collected movie magazines like STARLOG or FAMOUS

MONSTERS OF FILMLAND just to be able to see pictures of those beloved films,

and discover new ones. In those magazines, I would see ads for 8mm and Super 8

reels that would condense in 12 minutes films like MAN-MADE MONSTER, HOUSE OF

FRANKENSTEIN or I WAS A TEENAGE WEREWOLF. I wanted very badly to be able to

have a taste of those movies, but 12 minutes seemed a rather disappointing

compromise, and I didn’t own a movie projector anyways.

|

| One of the full page of ads for 8mm and Super 8 highlight reels of popular films, as seen in this case in an issue of FAMOUS MONSTERS OF FILMLAND. |

In the

mid-fifties, a particular trend was appearing in Europe: Inspired by Italian

fumettis (Original comic book-like stories made out of photographs instead of illustrations),

Franco Bozzesi started publishing in France hundreds of magazines that would

condense a film in a series of roughly 300 images, offering the chance to

French speaking fans to rediscover such films as GONE WITH THE WIND, JOHNNY

GUITAR, GORGO, THE H-MAN or MASTER OF THE WORLD. There were many different

series, each focused on a certain genre. STAR-CINÉ BRAVOURE (lasting from 1955 to

1974) specialized in action and then turned its attention to the then wildly popular Spaghetti

westerns. STAR-CINÉ AVENTURES would focus on American and Italian westerns

(Including THE GOOD THE BAD AND THE UGLY), and also ended its course

in 1974. STAR-CINÉ ROMAN started in 1958 and focused on more classical films

like LAWRENCE OF ARABIA or REBEL WITHOUT A CAUSE. From 1961 to 1965, STAR-CINÉ COSMOS (my

own personal favorite) would publish monthly 86 issues based on Science-fiction, B-Movies

and Japanese Sci-fi, and during the same period, STAR-CINÉ VAILLANCE would

cover war movies and sword and sandals epics. STAR-CINÉ COLT and STAR-CINÉ

WINCHESTER, from 1969 to 1973, rode on the wave of Italian westerns like DJANGO

and its ilk.

|

| An issue of STAR-CINÉ COSMOS, featuring an adventure from Japanese Superhero STARMAN, aka SPACE GIANT. |

|

| Three other issues in the ''STAR-CINÉ'' series, featuring RIO BRAVO (Howard Hawks, 1959) , LAWRENCE OF ARABIA (David Lean, 1962) and GUNFIGHT AT THE O.K. CORRAL (John Sturges, 1957) |

The fad continued in France in 1972 with a short 8 issue run of a similar kind of magazine published by Skandia retelling the story of 8 specific episodes from the Gerry Anderson TV show U.F.O., while another magazine called simply WESTERN would adapt in this photo-novel style 6 different Italian Westerns.

|

| Issue 6 of UFO, based on the 1970 Gerry Anderson classic show. |

The last gasp of the genre came with another Skandia publication, named simply FILM HORREUR, which in 1975-1976 had the time to adapt in a similar pattern 10 horror films, including Terence Fisher’s BLOOD OF DRACULA and Roger Corman’s THE PIT AND THE PENDULUM.

|

| The photo-novel adaptation of Terence Fisher's BLOOD OF DRACULA (1958) |

Most of those

magazines were shoddily printed and cheaply produced, and could be seen as not-so-distant relatives to comic books, even using word balloons and

onomatopoeia. No matter what, they were thrilling

for young French speaking movie fans like me who had few chances to watch at

will a decent monster movie or a cheap Japanese superhero fantasy. Needless to

say, I cherished every issue of STAR-CINÉ COSMOS I could put my hands on.

STAR-CINÉ

COSMOS would merit from MIDI-MINUIT FANTASTIQUE magazine’s Michael Caen, the

following compliment: ‘’Fantasy films, which lives on our screens for only a

season, can now be browsed at any times by readers in a truly unique series’’.

Meanwhile, back in the United States in 1963, artist Russ

Jones dreamt of bringing back EC Comics, but after being brushed off by EC

Comics ex-publisher Bill Gaines, who was still burned from Fredric Wertham’s

witch hunt, he opted to talk to Bill Warren, whose Warren Publishing did

wonders for horror with their popular FAMOUS MONSTERS OF FILMLAND magazine. He recalls

the meeting: ‘’I tried to sell Warren on my great plan to revive EC Comics, but he

resisted. He told me he had a plan to publish film mags in comic form, using

photos rather than art. We chatted for a time, and as I was leaving to head

cross-town, I knew that something was going to 'click' with Warren. I just felt

it.’’ Russ came back

later with his buddy Wally Wood, to try to impress further on Warren: ‘’Well, I think my first score with Warren

was The Mummy' comic book job. I wanted it to run at least eight pages, but Jim

said it would be six...or nothing. It was six. This was to run in Famous

Monsters, but sat on the shelf for quite a long time. Jim liked it, but comics

still frightened him. For some reason, he believed the dreaded 'Code' would

start to pry into his territory. The next assignment was the redoubtable HORROR

OF PARTY BEACH, photo/comic magazine.’’

|

| Russ Jones and Wally Wood's stunning (albeit short) adaptation of THE MUMMY (karl Freund, 1932) for Warren. |

|

| The 1964 Warren magazine that almost broke Wally Wood. THE HORROR OF PARTY BEACH (Del Tenney, 1964). |

Warren went

back for his ‘’comic book using photos instead of art’’, and sent Wally Wood

and Russ Jones on assignment. Sitting through the movie was a bewildering

experience for Jones and Wood, and after the experience of putting together the

PARTY BEACH magazine, Wally Wood wanted nothing to do with Warren anymore.

Jones, still hoping to resuscitate EC Comics through Warren, kept working for

the publisher, this time doing a photo adaptation of THE MOLE PEOPLE, for which

he was given the mission of pulling frame blow-ups himself from a 35 mm print

he had picked up through heavy security at a Pathé film lab in New York. Back home, he was surprised to find out he had been given by mistake a copy of the negative, which of course is not meant to

be touched. Some calls were made and the mistake was fixed, but not without a certain amount of stress involved.

|

| The second photo-novel adaptation by Warren. THE MOLE PEOPLE (Virgil W. Vogel, 1956) |

Meanwhile,

he created another short adaptation, this one with Joe Orlando, of THE MUMMY’S

CURSE, which was published in MONSTER WORLD #2 (THE MUMMY strip had been

published in issue 1), and also short strips of THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN and

HORROR OF DRACULA, which ended up being published in issues of FAMOUS MONSTERS.

The same two Terence Fisher films were the subject of the last issue of FAMOUS FILMS, where

Warren’s adventure into fumetti ended. Jones had finally convinced Warren that

a horror comic was viable again, and started work on the legendary CREEPY magazine.

This opportunity to have a film accessible at

our fingertips, just by reaching into our bookcase, finally achieved a sense of

legitimacy when the gorgeously produced books edited by Richard J. Anobile appeared

in libraries in the early seventies. Ads for the now celebrated Film Classics

Library would pop up in those last pages of FAMOUS MONSTERS OF FILMLAND next to

the ones advertising the super 8 one reels of monster movies.

Between 1970 and 1982, the name Anobile became synonymous to stunning movie books that treated cinema with a mixture of reverence and accessibility. Both scholars and regular film fans could fully enjoy them, and it’s a crying shame that such books have completely vanished from the shelves by now. (However, industrious fans can still find some of those prized volumes on sale on the internet.)

I have managed to get in touch with Richard J. Anobile,

who has been keeping busy as a Post-Production supervisor for the last few years,

after decades as a film and TV producer, notably on Guillermo Del Toro’s THE STRAIN.

Born and raised in New York, young Richard Anobile

was fortunate enough to grow up during the dawn of television, which used to

broadcast regularly ‘’tons of old

movies – especially comedies – Laurel and Hardy, Chaplin, Marx Bros. Fields,

Abbott and Costello, etc.’’ that

he would watch with constantly renewed pleasure. He watched local Memory Lane

shows with New York broadcast legend Joe Franklin as moderator (and much later

was thrilled to end up on his show for interviews when his early books were

published.) ‘’I would imagine that all of that exposure to early film led to my

interest in entertainment – never really thought of film as art until I was

older – late teens – then, of course, got into the incredible availability in

NYC of various art houses playing Bergman, Fellini, you name it. ‘’

He studied cinema at the City University of

New York, a public, and more importantly, affordable institution. Being from a

‘’ lower-middle class

first-generation Italian-American’’ family, he just couldn’t afford the celebrated NYU film

course.

-BD: I would imagine that’s how DRAT! (Being the Encapsulated View of Life by W. C. Fields in His Own Words. Published in 1969) came about.

Even if this wasn’t the perfect school, it

did have a few things going for it; for starters, the CCNY Institute of Film

Techniques was considered the oldest film school in the US ‘’It served as a training school for wartime filmmakers during

WWII. By the time I got there in 1964 it

was just hanging on but still offered great courses and a lot of flexibility –

historian Herman Weinberg was one of my first teachers and I was drowned in the

film of Erich von Stroheim and other German filmmakers – as well as early US

filmmakers, etc. ‘’

As a student, he managed to produce a

documentary on Harlem, but he soon found that a lot of his time was going to be

invested in attempting to save the Institute.

‘’The President of CCNY was not very film oriented. He could never see

the connection between the mechanical aspect of film-making and its creative

aspect. He decided to seek out grants

from the Federal government for more teaching courses and wanted the Film

Institute building for those course – so he moved to shut it down. Most of the other students didn’t care one

way or another but I had finally made a decision to study film, rather than law

(my other possible alternative) and I wasn’t about to have him upset that apple

cart. So I ended up spearheading a drive

to save the institute. As this was

during the time of the creation of the American Film Institute, I was able to

draw a parallel between the two and found support from Vincent Canby – then a

writer for Variety, the local congressman – Bill Ryan – and the Mayor – John

Lindsay. It started quite a ruckus in

the media and we had a demonstration on campus where we projected films on the

bedroom windows of the President’s on-campus residence. He was not thrilled, but we did manage to

keep the program going another 2-3 years – but all courses were shifted to

night course and after a while I found myself going to college days and nights

– eventually I decided to focus on completing the film course and got a job at

the NY Times paid obit section’’.

This is where he got to rub shoulders with

acclaimed movie critics like Bosley Crowther, Abe Weiler, Howard Thompson ,

Vincent Canby and Roger Greenspun. A remarkable ensemble. ‘’I also had a part-time job with (film collector and distributor) Raymond Rohauer helping him mount retrospectives at the Gallery of Modern Art, the

(now defunct) museum at Columbus Circle owned by Huntington Hartford which

housed his famous Dali collection. I

worked with Raymond on retrospectives for Laurel and Hardy, The Marx Brothers

(when I met Groucho for the first time although just briefly), Rouben Mamoulian, you name it.

Rohauer had a contract with a book packager to write a book about Buster

Keaton, and well, he reneged on the contract and the publisher approached me to

do a film book…

(Side note: Jack Rennert – who was head of Darien

House, was a liaison in Congressman Bill Ryan’s office in Manhattan – the

congressman in whose district was City University. When I started rabble-rousing to save the

Film Institute, it was Jack who first contacted me – and that is how we

met. I then introduced him to Raymond

Rohauer and Jack did a deal with Raymond for a Keaton book – which never happened,

but led to Drat!– and Jack introduced me to Jane Wagner and The Harry Chester

Group – funny how one thing leads to another – so much for ‘planning’ a career!!)

-BD: I would imagine that’s how DRAT! (Being the Encapsulated View of Life by W. C. Fields in His Own Words. Published in 1969) came about.

-RJA: Yes.

Having realized how difficult it was to truly study film in college

unless one had the dollars to be able to rent 16mm prints – probably from Janus

Films, etc. I suggested recreating

scenes of W. C. Field’s films using frame blow-ups. That was considered too expensive –

especially with an untried author/editor, so it evolved into a juxtaposition of

still and quotes.

As this was my first book and I really didn’t

know yet how to approach things. I was fortunate to be paired with an editor

who was able to help me make sense of the objective and evolve a methodology to

achieve the desired end. Mostly I remember spending many weekends with Jane

Wagner drinking margaritas and watching Fields films and taking notes, then

collecting stills and marrying them with the quotes in a way that seemed

entertaining but at the same time captured the essence of the Field’s

character.

I was also introduced to the graphic design

team with whom I would work for many years on all of the frame blow-up books as well as

the book with Groucho: Harry Chester and Alex Soma. And having worked at the

Times came in handy as a NY Times Arts writer – Richard Shepherd, was a fan of

Fields and agreed to provide the intro.

In the end, Drat! Proved to be a great

success- who knew!!??

-BD: This

success paved the way for the book that would foreshadow the Film Classics

Library in its basic layout and style.

-RJA: Of course the publisher wanted another book –

that was my opportunity to push the frame blow-up concept and it resulted in

Why a Duck?

-BD: As an aside; What

did you think of ''fumettis'' like the French STAR-CINÉ magazine series that adapted

popular movies in a form closer to a comic book?

-RJA: I was

not really exposed to fumettis until after I started my work and I don’t recall

seeing enough to make a comparison. I believe my work was a bit more geared

towards fully realizing the intent of a scene, director’s style, etc., as I was

coming at it first as a tool for study. But it would be presumptuous of me to

try to, from this vantage point, compare my process to fumettis. The European

approach was certainly successful. In

hindsight it probably would have been a good idea to have steeped myself into

that process a bit more – as a learning tool – but I did not.

-BD: It most likely turned out for the best, as you were able to tackle this with a fresh, unencumbered vision. Having done the exercise of comparing your work on John Ford’s STAGECOACH for the FILM CLASSICS LIBRARY, and the French fumetti equivalent, there is a striking evidence of your more cinematic approach. You show your love of the film language, just in the way that you take nearly 6 pages to translate the same amount of action that the magazine does in one page. They even skip a classic stunt that you take the time to focus on in your volume.

|

| Compare this scene from STAGECOACH as published in the French Photo-Novel magazine STAR-CINÉ AVENTURES, with the way it is portrayed in Anobile's FILM CLASSICS LIBRARY edition of the same film. |

|

| 4 of the 6 pages that Anobile spends on portraying the same scene in his volume from FILM CLASSICS LIBRARY on the 1939 John Ford Western classic. |

- RJA: The stunt work on STAGECOACH, as you know, was quite incredible. I just couldn’t pass that up, and that is part of what makes cinema so fascinating to watch. And (stuntman) Yakima Canutt’s work in STAGECOACH was, in some ways, precedent setting. Especially as the Indian shot as he wrangled the head team of horses. Running the bits of these types of scenes over and over to try to capture the cinematic quality of the movement between the frames I had chosen as placeholders was tedious and I could never be sure I had it, or that it would actually translate for the reader.

Trying to isolate a particular piece of action so as to convey continuous movement was a challenge. It was always a stretch to push for this sort of non-verbal presentation. Fortunately, between the strong support I had at Darien House from Jack Rennert (its owner having published a number of Illustrated Art and Poster books) and the support at the group of publisher’s involved – especially Avon Books – I was allowed to indulge in this sort of detail.

- BD: An interesting esthetic choice you make in the books is to have frames that signify cross-fades, in an attempt to be as close to the film language as possible.

|

| A striking example of the use of cross-fades in the books, from PSYCHO (Alfred Hitchcock, 1960) demonstrating a love and respect for the cinematographic language. |

-RJA: Well, the FILM CLASSICS LIBRARY was meant to truly represent film in book form and I felt strongly that I had to retain that sense of film-motion, film-transitions in storytelling – despite the static form of the page – if I wanted to keep the pictures ‘’moving’’. Especially as I knew the reader was also needing to focus on the dialogue, something that is automatic when viewing a film – so there always was a real push-pull between moving image and the demands of the page.

|

| Advertisement |

-BD: I can imagine though that convincing a publisher to go ahead with producing a book made almost entirely of photographs, a rather expensive process, was a difficult task.

-RJA: As

with most people trying to push a new idea – one that had not been tried with

film material to the extent I had in mind (Europe did have what we would now

label graphic novels and – to a degree as you have mentioned, there was

Fumetti). I discovered that my idea was easier pitched then done. I

literally had to establish a way forward – an m.o. for how to best accomplish

the goal. For Why a Duck and for the first few frame blow-up books I did, I worked on a Moviola

– not the most comfortable or compatible machine for doing what I needed to do

– but it was all I had available to me at the time – this would have been

around 1969-71.

As Why a Duck would be using films controlled by Universal (even the early Paramount films, except Animal Crackers which was tied up in litigation at the time) I was invited to spend time on the Universal lot in a cutting room with a Moviola and a pile of prints of the films. I would work reel by reel watching and re-watching scenes – making notes for myself and use a grease pencil to mark the frames I wanted to have printed – hundreds of frames from each film. Frankly, I was scared shitless as I wasn’t sure I knew what I was doing and this was an expensive process; it had to be handled by the Universal lab. The head of Universal Post Production – a fellow named Chuck Silver – took an interest in what I was doing and made sure I was comfortable and that everything I was doing would be easily translated into stacks of prints organized by reel and edge code. I spent about 2-3 weeks in LA on the Universal lot, living in a room at the Chateau Marmont and when I was done, Chuck had the prints shipped off to the lab. I flew back to New York – my home town – to await the stills.

|

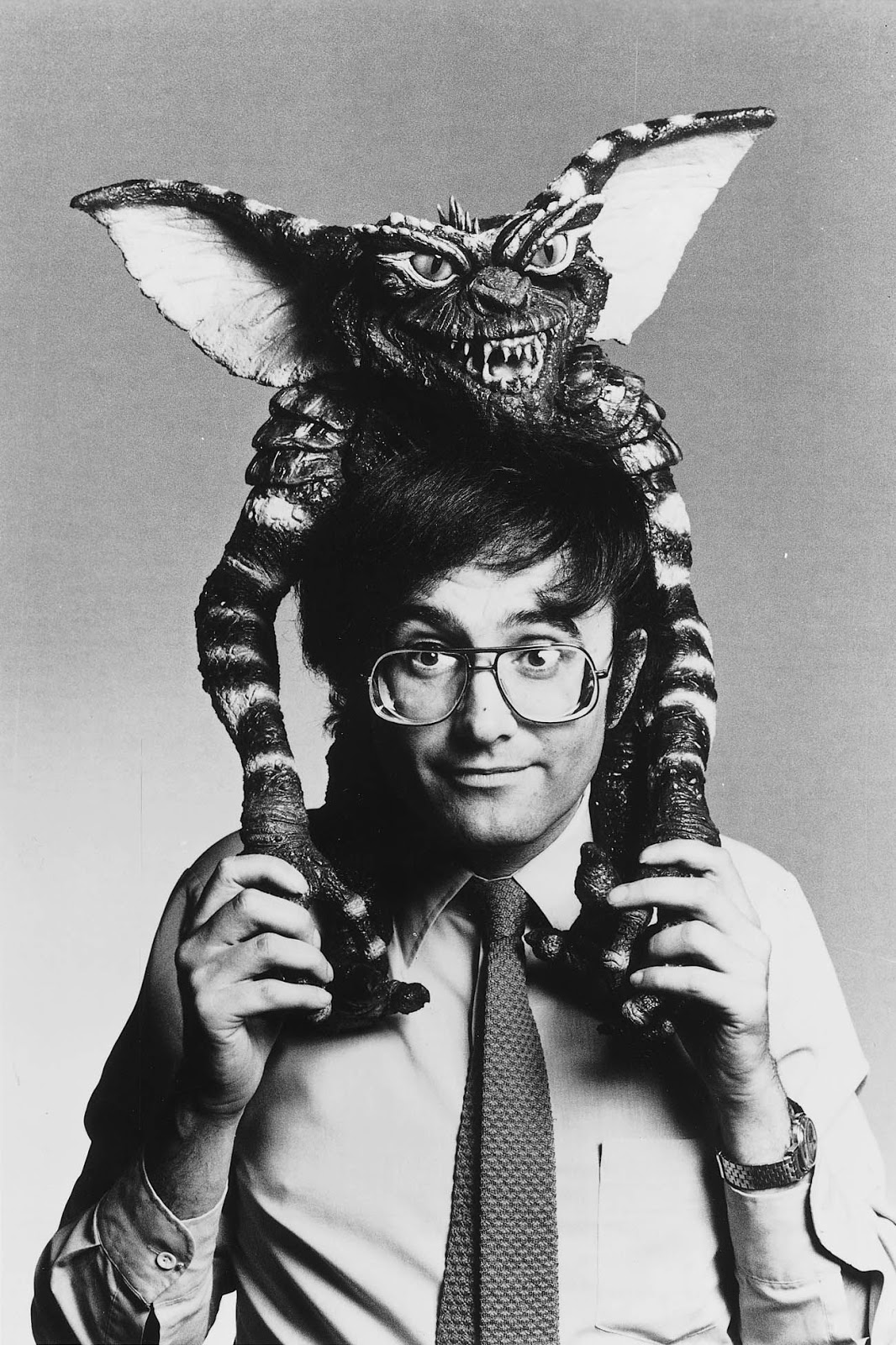

| Richard J. Anobile in a Fifth Avenue Screening room in New York, during his film reviewer years, circa 1971. |

As Why a Duck would be using films controlled by Universal (even the early Paramount films, except Animal Crackers which was tied up in litigation at the time) I was invited to spend time on the Universal lot in a cutting room with a Moviola and a pile of prints of the films. I would work reel by reel watching and re-watching scenes – making notes for myself and use a grease pencil to mark the frames I wanted to have printed – hundreds of frames from each film. Frankly, I was scared shitless as I wasn’t sure I knew what I was doing and this was an expensive process; it had to be handled by the Universal lab. The head of Universal Post Production – a fellow named Chuck Silver – took an interest in what I was doing and made sure I was comfortable and that everything I was doing would be easily translated into stacks of prints organized by reel and edge code. I spent about 2-3 weeks in LA on the Universal lot, living in a room at the Chateau Marmont and when I was done, Chuck had the prints shipped off to the lab. I flew back to New York – my home town – to await the stills.

Well, after

a couple of weeks or so nothing showed up so I called Chuck and he looked into

the progress at the lab. Well, he sheepishly called back telling me that there

was a big problem – the lab decided to clean the prints to ensure the stills

would be as good as they could be, and well, all my marks were gone – I had to

start all over again. Off I went back to LA and followed the same process

all over again. But, the silver lining was that this time I had a better

understanding of the approach and a better sense of what I was looking for.

That initial ‘’dry run’’, so to speak, was a fabulous learning experience –

though initially it did not seem so. I learned what to look for in the stills

– frames – gestures, looks, composition, eye contact, subtle attitudes that

managed to somewhat reproduce the feeling of the material. So, in essence, I

lucked out as I am not sure my initial work would have yielded the successful

enterprise that was Why a Duck – it established the frame blow-up approach as valid and it created a

career for me – and it led to my next meeting with Groucho which led to The

Marx Brothers Scrapbook. And it

strengthened my hand for finally getting The Film Classics Library off the ground. I continued

with the comedy books - finally getting the rights to do Animal Crackers – and books on Fields, Laurel and Hardy and

Keaton, etc.

-BD: Speaking

of THE MARX BROTHERS SCRAPBOOK, which you authored with Groucho Marx himself, how was the experience of working with the comedy legend?

- RJA: Well, you can imagine

that I was scared shitless when I found myself about to embark on something I

had never done before – interviews for a book (in fact the book was to have

been a more formal biography but as I was doing the initial interview I

realized I would never be able to truly capture Groucho’s ‘‘voice”, so I went

back to the NY publishers through Darien House and essentially told them that I

would deliver a Q&A format – and that the photos collected for the book

would be arranged in the sequence of the various interviews – hopefully broken

somewhat into decades. I had a sense of what I wanted to accomplish- but no

experience or confidence that I would ever get there. It was daunting.

Here again I was

fortunate to have had a test period.

The editors at W.W. Norton were not quite convinced that Groucho had a book in him – age,

faulty memory, frailty, etc. – so they would only pull the trigger for the full

book once they had a sample chapter. I

went out to LA for a month – and this sample chapter ended up being the one focusing on Night of the Opera. It was

set up so that I would work with Groucho a few days a week, in the afternoon

at his home in Beverly Hills on Hillcrest drive. I can recall how daunting it felt to pull up

to his home that first day – ring the bell and find myself greeted by Groucho...

|

| The one, the only, Groucho. At home in Beverly Hills circa 1972. |

I should digress a bit

– after Why a Duck was published, Groucho’s agent had set up a dinner meeting

with him and (Groucho's assistant) Erin Fleming. The book was successful, Groucho

loved it and this was a way of his thanking me. The three of us ate in a restaurant

just at the Beverly Hills line on Sunset Boulevard –and as it turned out, it

was not far from his home on Hillcrest Drive.

We spent about 2 hours or so chatting and dining and somewhere along the

line I realized that the history of modern American comedy was wrapped up in

this man. So I asked him if he would consider a book about the Marx Brothers. He

said something to the effect that if there was a publisher crazy enough to want

it, he would work with me on it. I took

that answer back to NYC and Jack Rennert of Darien ran with the idea and

brought on publishers in the States and England who wanted the book – now I was

really stuck!

Anyway – another

fortunate happenstance for me was that Jane Wagner, the editor who had guided

me through Drat!, was going be my editor for The Scrapbook.

She was a fabulous

woman – bit if a foul mouth, quite a character in her own right (had been a nun

who left the convent!) and had worked with Rennert for a bunch of years – in

fact, they were involved in NYC upper west wide politics together and worked

hard against the Vietnam war – I believe they helped in the winning campaign to

get Congressman Bill Ryan elected, a strong opponent of the war. Anyway she was

a fabulous editor who had worked for various houses and she was incredibly

helpful to me – especially as I did the first taped interviews with

Groucho. She sensed I was frustrated and

kept attempting to pry out answers. She would listen to the tapes and as they

would be transcribed she was starting to get a sense of the story. She called

me one night and reminded me that Groucho was in his eighties; I needed to give

him time to think, to collect his thoughts. I can still hear her telling me, ‘’Richard

– tape is cheap, let it run – don’t feel you have to jump in, you are not doing

a live broadcast – dead space on the tape is okay’’. Jane was about 20 years older than me and her

words at first seemed like a reprimand. But I realized how valuable her insights

were the next time I met with Groucho. I

let the tape run – and little by little the memories flooded back to him and

his words grew more voluminous – more descriptive – more friendly – more

naturally Groucho. And he started enjoying the process and wanted to get a lot

off his chest. In a way, this trial run

at creating a sample chapter had the same impact as the cleaning of the grease

pencil marks from the 35mm prints for Why a Duck?

It allowed me to grow,

understand the approach and it relaxed me – I was finally in conversation

rather than ‘‘doing interviews’’. When

I got back to NYC, all the tapes had been transcribed and I could start putting

the conversation in order and assembling photos – but not confident that I was

a good enough author/editor, I insisted on trying to keep things as they were

recorded – unless I had to go back on another day for clarification about

something we had discussed (which was

something I did regularly as we got into the balance of the book later on, after

I would get supplementary interviews to check Groucho’s memory against. If

something did not jive, I could play him Jack Benny’s comments, or Gummo’s

comments, or whoever, and have him give some thought to what they were saying –

then get clarification – or verification.

I had researchers

working in New York and London and between my research and theirs I had

assembled a series of index cards laying out the team’s progression from

childhood to burlesque to vaudeville to stage, screen and radio and finally,

Groucho to TV. Imagine Groucho has

touched every form of modern American/North American entertainment medium –

well, not the net – except belatedly.

|

| Groucho Marx chatting with Richard J. Anobile circa 1972-1973, for the MARX BROS. SCRAPBOOK. |

-RJA: The falling out was

quite sad. If you have read the book you

may have noticed that Groucho could use some salty language and held some

strong opinions. This was 1972-73 and it

was still, in some ways, the 60’s. I was part of that culture that pushed

against boundaries, and as I read through the transcripts and put things

together it struck me that, even without the kind of journalistic background

that might have been helpful to have for such a project as this, I had managed to capture Groucho’s ''voice'’. Not

just on tape, but on the page. Groucho’s

humor was in some ways radical. He was, in his own way, an anarchist: he revelled in deflating the pompous, the politicians, the wealthy, etc. And he set

the style for an almost dominant American strain of humor that carries on to

this day. Think of Seinfeld, Larry David, and some of the late night performers giving

Donald Trump the metaphorical finger every night. Anyway, I didn’t want to lose this and I left

a lot of the blue language and strong opinions in the book, and the publishers

supported this. Groucho did review the

‘blues’ of the book and even made some changes.

The book went to press

and one of the first copies was sent to Groucho – and his family – they had

never paid attention to what we were doing, never came by his home in the three

months I was there - they freaked and hired lawyers to stop the book from being

published claiming that it was obscene and defamatory, etc. The shit hit the fan and when I tried to

reach Groucho I could not get through to him. Erin Fleming did pick up the phone one day to

remind me that « Groucho has a family. »

|

| Groucho Marx with personal assistant Erin Fleming. Fleming became Groucho's close companion from 1971 to his death at 86 in 1977. Their relationship was controversial and some, including son Arthur Marx, felt she was pushing the aging comedian past his capacities by arranging personal appearances, a sold-out Carnegie Hall performance, and many other activities which had at the time revived his popularity. While she was cleared by a psychiatrist as someone who worshipped Groucho and just wanted to help him out, without any interest in obtaining financial gains from those ventures, litigation over his estate still ended up in favor of Marx' son Arthur. In the meantime, a lovely moment from Dick Cavett's show where they sing together HELLO, I MUST BE GOING. |

The first edition of

the hardcover had already shipped to stores and Penthouse Magazine was about to

ship its December issue featuring an interview with Groucho, an excerpt from

the book. (Penthouse founder) Bob Guccione wasn’t about to let his magazine

languish in a warehouse (this was at the height of the Playboy-Penthouse

competition for readership) so he went to court and had the injunction against

sale overturned on the premise of ‘prior restraint’ not being legal. He won that day. The press latched on to the

story and the book became a bestseller overnight.

The WW. Norton first

edition sold out but they would not go back to press as the Publisher was

pissed that he had published a book he couldn’t give to his children. Darien House had to find another publisher

and the second edition was published in the States by Crown Books – the legal

case continued and I found myself having a group of attorneys and having to

undergo interrogatories, etc. Not

pleasant. And Groucho’s lawyers kept basically lying saying that he had never

said what was printed. But when I showed up in court with the tapes they

changed their tune to: well, he didn’t know it was going to be published. When

the court was given the ‘’blues’’ with his signature on every page, they

changed their tune again. It was never-ending

and very expensive.

However, the lawsuit really served to make the book a

great success here and in Europe (WH Allen published in Europe). Eventually

Grosset and Dunlap published another edition and Warner Books published a paper

back with the banner at the top claiming « this book is worth 15 million

dollars » which is what I was being sued for. As if I had it. (Fortunately, thought it did not seem

so initially, I was not receiving royalties for the book, just a fee – Groucho

received royalties – which worked out, as the publishers footed my legal fees.)

Long story short, it

ended my relationship with Groucho and to this day I still wonder if I did

something wrong. But I really am proud of the book and it does capture the

essence of the team and certainly, Groucho, and I hope it means something to

anyone reading it today. I have renewed the copyright as an author and the

original tapes are housed at The Academy Library in LA.

Groucho died before the

suit was settled and his family dropped it as they couldn’t divvy up his estate

until the lawsuit was over.

-

-BD: Moving

on to WHY A DUCK?, there is a distinct stylistic layout change between it and

the following books. What brought upon that change?

-RJA: You have to understand

that those books cost more than the usual picture-based books as the frames had

to be created at some cost – it was a time-consuming process. And working

with the designer to work out the best layout for flow and continuity was

another time-consuming part of the process as I would constantly be reviewing

the layouts and, of course, upending everything by making changes in position,

sizing, over composition, etc., until I felt that the flow was true to the

scene and would make sense to the reader as the pages were turned. As I

went from book to book – and then to the Film

Classics Library the layout approach kept

evolving – initially just from my sense of things from comments by those involved in the production of the books – then from reader feedback – and

editorial feedback. In a sense each subject had demands of its own that

had to be married to the layout/design process and contained within a certain

number of signatures and pages.

-BD: How did you pick the films

that ended up part of the Film Classics Library?

-RJA: The Film Classics Library had to be

approached both as a tool and a commercial venture so I had to find titles that

were classics but that had broad appeal. Originally I had planned a series of

24 titles (Ended up being 9 in total: FRANKENSTEIN, CASABLANCA, PSYCHO, NINOTCHKA, STAGECOACH, DR JEKYLL & MR HYDE, THE GENERAL, THE MALTESE FALCON) – didn’t quite get there as technology encroached. And some people were

pissed off that I had chosen to do the Fredric March version of Jekyll and

Hyde rather than the Spencer Tracy version. BIRTH OF A NATION was on the

list, SUNSET BOULEVARD, PATHS OF GLORY,

etc. I just never got there.

-

-BD: Which

was the most challenging film to translate to book form? I noticed that THE

GENERAL by Buster Keaton seems to be the longest volume of the collection with

over 2100 images.

-RJA: Getting The General done was a bit of a miracle - it was the

one title I was asked to consider dropping – but I was stubborn and the series

was successful enough that I had some leeway. But it probably was the most difficult

to translate/reproduce. First, because it was silent, and then the nuance of

Keaton’s work, the expressiveness of his performance – all incredibly difficult

to capture. There were times when I felt I would fail at this one and

considered announcing that possibly the editorial team was right: (I should)

skip The General. But, I really loved that film and in my heart I consider

Keaton, rather than Chaplin, the preeminent comic filmmaker. I soldiered

on and was fortunate to have such support from my design team – and especially

from one on the team, a fellow named Alex Soma who was quite a film historian

in his own way and he labored with me on it until we thought it worked.

- -BD: It’s a wonderful book, and I have to agree about Keaton being one step

ahead of Chaplin as a comedy genius. I love Chaplin, but Keaton used film in a

truly cinematic way, while Chaplin tended to be more theatrical. You moved on

after the Film Classics Library to

color adaptation of films. How did this come about?

-RJA: I would have

to say that at some point in the process I was starting to get fatigued – I

felt that I had honed the process to a point where was not able to be much more

creative and that there was little more I could do to better refine the end

product. Interestingly

though, the studios were approaching me to do tie-ins and I started

working with a close friend in LA, Ryan Herz, who was a photographer and who was able to

come up with an economical process for me to start handling color and wide

format (anamorphic) films, the first one being Ridley Scott’s ALIEN. Fox had wanted me to

do STAR WARS, but Lucas wouldn’t

approve the project so they handed me the script for ALIEN – which they were about to start shooting

and suggested that I could work on the book version in tandem with the film version

so that the book could be released just after the film’s premiere. And that is

what basically happened. The book was the best way for anyone to get a solid

look at the creature, it was a commercial success and it was a technical

phenomenon in publishing – over 1000 full color anamorphic frame blow-ups in a

book that only cost about eight dollars. Avon Books was the publisher (they

also did the Film Classics Library)

and they had a heart attack when they heard that this would be full color.

It would put it in the realm of a very expensive art book to manufacture. But I

had been talking with some of their production specialists who had found that there was a process of color

separation that could be done by page, rather than by photograph. Instead

of over a thousand or more color separations, the book could be printed using

only 164 color separations. Essentially the number of pages in the book.

The designer – again Harry Chester Group – had to work with me to lay out the

pages so that the story could be told but in such a way that facilitated the

color separation process – not only was the book very successful, but it won

printing awards within the industry. And it opened the door to more full

color books (Two other full size books were produced by Anobile: Robert Altman's POPEYE and Peter Hyams' OUTLAND).

-BD: it safe to assume that home video also contributed to kill your book

series? They seem to have disappeared at roughly the same time VHS and Betamax

became popular.

- -BD: In 1978,

Bantam books published a series of STAR TREK “Fotonovels” adapting episodes in

pocket book form, (Often attributed to you on the web, although I see no

evidence of it in the books credits) seemingly stealing your act. Did this

prompt the format change to the smaller paperbacks, like it did for your MORK

AND MINDY Video Novel and BATTLESTAR GALACTICA Photostory, and what did this

mean creatively for you?

|

| Competition came strongly from the FOTONOVEL series, which stole Anobile's thunder with a focus on more popular fare. A 1978 article by THE WASHINGTON POST implies that they outsold Anobile's FILM CLASSICS LIBRARY. "When you're doing Buster Keaton in 'The General,' you can't expect to sell a lot," says Robert Wyatt, editorial director at Avon. "We talk about doing something like the Fotonovels every few weeks now. But you have to realize you have to start with a lot of copies when you print that much color. If you print 500,000 you could eat 300,000 books if it doesn't go." |

- RJA: I did produce two STAR TREK photo novels – THE MOTION PICTURE and THE WRATH OF KHAN. (But not the ones based on the TV series). But, yes, formatting

for paperback meant some compromises, different choices of how to focus on a

frame due to size. But also this was not being done for any type of study. Just

for fans, for marketing, for fun. I

never did another STAR TREK book because I delivered a full color book for THE

WRATH OF KHAN, but the publishers decided to print in black and white – and I

was given shit for it by fans though it was not my decision. And that was that. As to the others -for fans, for fun – really

these were marketing tools (did I sell out a bit? Well, earning a living is important.

Especially, as by then – if I have my dates straight- I had moved to LA and was

hoping to find my way into film production.)

Even the full-sized OUTLAND and POPEYE were coffee table marketing

books. Essentially they paid the rent – and I was basically done – my head was

elsewhere and my focus was on different things.

Yes, VCR’s

essentially meant there was no need for the type of book I had been creating. Really,

why would you need a book of frame- blow-ups when you can have every frame of

the film (with sound!) and play it over and over, stop, start, freeze frame,

etc.? Had VCR existed when I was in school I would never have thought

about frame blow-up books – they were meant to be a study tool. It just so

happens they were popular for a time with a more general public of book buyers,

for whom I have a lot of gratitude. Those fan-buyers gave me my first

career. And, let’s face it; how much longer could I be doing the same

thing over and over. So for practical purposes: yes, VCR was, to my mind,

a death knell – but also a welcome one – it got me off my ass towards trying to

realize another goal.

-BD: This is when you started working in film production?

-RJA: By that point, the writing was on the wall. And frankly I was getting bored. I wanted to finally do what I had studied film to do – work in production. So I quit publishing and practically went broke trying to get my first job in film. I foolishly turned down some offers to work in PR both at Paramount and Columbia as I was focused on production – a big mistake and when I am asked today, I tell film students to grab any job they can get. Get that foot in the door, then navigate from within the industry. I also suggest that they study entertainment law, then get into film, no matter how creative they want to be – it is vital to understand the complexities of the medium.

-BD: This is when you started working in film production?

-RJA: By that point, the writing was on the wall. And frankly I was getting bored. I wanted to finally do what I had studied film to do – work in production. So I quit publishing and practically went broke trying to get my first job in film. I foolishly turned down some offers to work in PR both at Paramount and Columbia as I was focused on production – a big mistake and when I am asked today, I tell film students to grab any job they can get. Get that foot in the door, then navigate from within the industry. I also suggest that they study entertainment law, then get into film, no matter how creative they want to be – it is vital to understand the complexities of the medium.

I never did

reach where I had hoped to be but I certainly can’t complain about my

‘‘career’’ in film – or rather TV (only time I brushed against features was as a

Production exec at Paramount for just under two years – after that it was all

TV.) Coming to Toronto initially as a Production Exec for series shooting

here (on a show called Cat Walk) was also fortuitous. When I had the chance to go back to LA –

even stay in production – I realized I never did like LA or most people I had

met in the business, but I did enjoy the film community here in Toronto. Though

I had to find a different way of working and eventually evolved into Post Production,

which I thoroughly enjoy. I love managing projects, working with teams and

seeing all the pieces successfully married. It is a wonderfully creative

process.

And, look at

that – I got to spend four seasons on a show with Guillermo Del Toro. What a fabulously

creative mind and a truly terrific person. I am not known for doing

features so he used someone else for that, hence I missed out on THE SHAPE OF WATER. But as we did the VFX for

Strain also at Mr. X, I got to sit in on a bunch of

Shape sessions as well. No one realizes that those eye are all done here at Mr.

X, as well as the water pouring out of that room – all digital – some

incredibly wonderful work. Same thing with THE STRAIN. And Guillermo’s eye is impeccable; he will notice

something even in the corner of a frame and want it addressed, even when I

would say: ‘’But Guillermo, it is out of picture safe!’’ But HE would know, and

that’s what really mattered.

And I have

gotten to live in a great city that has become better and better as the years

have gone on – and in quite a terrific country as well – one that is Trump-free

– and let’s hope it stays that way. And I am married to a wonderful

Canadian woman – so no complaints.

|

| Richard J. Anobile in 2016 at the Sherwood Inn in Muskoka, Ontario. |

There is an

obvious love for the art of cinema, and a willingness to share its style in

full integrity, including lap dissolves and fades, and emulating camera

movement by careful choice of successive frames, in every one of Anobile’s

books, especially in the case of the FILM CLASSICS LIBRARY. While they may now be

considered obsolete, they have long been indispensable for film scholars and

students. Something like the 20 pages spent on dissecting shot by shot the

murder scene in PSYCHO is worth volumes of analysis for an editor like I am.

And there is still an undeniable pleasure to peruse through those books, taking

the time to savor multitudes of moments frozen in time, like Boris Karloff icy

stare after his big reveal as the creature in FRANKENSTEIN, or the longing

glances between Bergman and Bogart at the end of CASABLANCA.

Richard J.

Anobile never had any illusions about the sustainability of his books. In his

preface to A FLASK OF FIELDS, in 1972, he could already see the writings on the

wall; ‘’I don’t expect these books ever to take the place of films. But until

such time as the films become more easily available for home viewing, we will

have to settle for sporadic film festivals and a book such as this. This book

is merely designed for you to have fun while reflecting upon the artistry of a

truly great comedic mind.’’

In the

meantime, reading one of the FILM CLASSICS LIBRARY still provides us with a

glimpse into the mind an exemplary film lover who toiled for years to bring the

silver screen to every home in its own way.

In the second part of this series, we will focus on comic book adaptations of movies, and discuss with Stephen Bissette on his work on Spielberg's 1941. See you then.

In the second part of this series, we will focus on comic book adaptations of movies, and discuss with Stephen Bissette on his work on Spielberg's 1941. See you then.

Man! There was so much research in this post! I'm impress! You really have a knack for getting into your subject. This is pretty good skeleton for a university-level thesis on a forgotten aspect of pop culture. I remember parts of it. I had some Star Trek photonovels and maybe a couple of those UFO magazines in my teenage years. And I've seen the Anobile books. I have to hunt down one of thoese Star-Cité magazine about RIO BRAVO and that STAGECOACH volume by Anobile.

ReplyDeleteThanks, Kid! I'll keep my eyes peeled to see if I can catch some of those in the wild. ;)

DeleteThank you for this interview. I was a kid in the 70's and used Anobile's books to supplement my love affair with movies whenever there was nothing available on the local television airings. I've also always wondered about the inside story between Anobile and Groucho, and how that whole dispute evolved. Now I have the inside scoop from Richard himself. I would love to see Richard do a book about his experiences with Groucho from A to Z, something like Steve Stoliar's narrative of his years inside Groucho's house.

ReplyDeleteI am most curious about the tapes that Richard made of his interviews with Groucho. Does Richard have sole rights to those tapes? If so, did he ever consider publishing them—either in audiobook form or on YouTube? I think that would be a fascinating listen.