Before Home Video Part 2: The Comics / STEPHEN BISSETTE INTERVIEW

In the first part of this series, we looked into the practice and publications of Photo-novels and

fumetti, (along with an interview with Photo-novel giant Richard J. Anobile) which were

one of the best ways to recapture the experience of watching a film at a

time where owning your own copy wasn't an option, and you had to hunt down listings at the repertory theaters and in the TV Guide for chances to see your favorite films.

Movie soundtracks also provided an interesting compromise, but the narrative remains missing, and of course, the all-too-essential visuals. The music can of course evoke beautifully the film it was composed for, and bring back fond memories of the experience, but it remains a completely different way to relive a movie. Combining reading a Photo-novel version of a film with its music soundtrack can be, however, an oddly satisfying, yet frustrating experience, as the mood can be re-created, but the music may not follow the pace of reading.

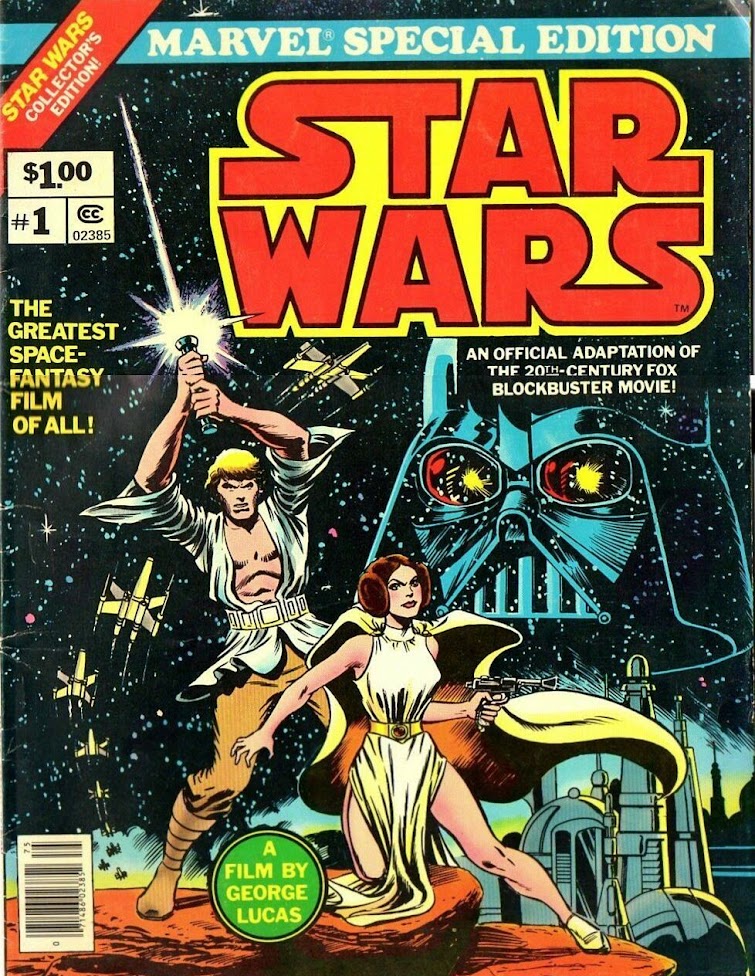

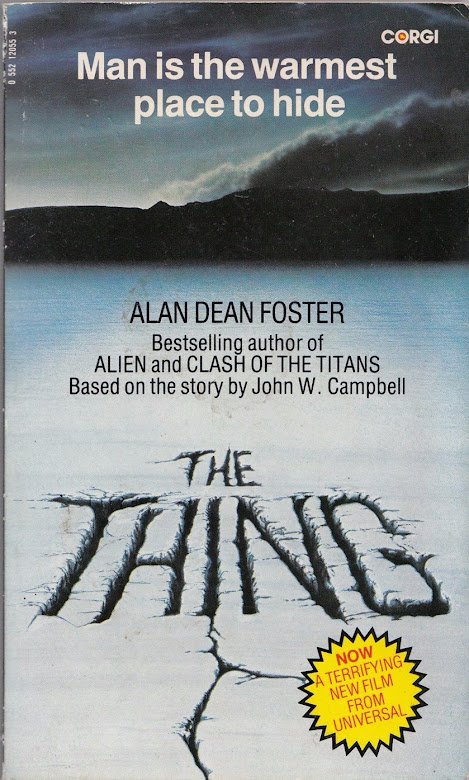

Then there were the novelizations, in which movies are retold in prose form. Something that may be somewhat satisfying in a somewhat more cerebral way, but never can do justice to visual extravaganzas like THE THING, ALIEN or STAR WARS, no matter how talented frequent novelization author Alan Dean Foster is. The books however can offer additional insights by stepping into the minds of the main characters, as well as offering untold details in the narrative, since most are based on earlier versions of the scripts, which often makes them an interesting addition to a film, all the while failing as a satisfying replacement.

Movie soundtracks also provided an interesting compromise, but the narrative remains missing, and of course, the all-too-essential visuals. The music can of course evoke beautifully the film it was composed for, and bring back fond memories of the experience, but it remains a completely different way to relive a movie. Combining reading a Photo-novel version of a film with its music soundtrack can be, however, an oddly satisfying, yet frustrating experience, as the mood can be re-created, but the music may not follow the pace of reading.

Then there were the novelizations, in which movies are retold in prose form. Something that may be somewhat satisfying in a somewhat more cerebral way, but never can do justice to visual extravaganzas like THE THING, ALIEN or STAR WARS, no matter how talented frequent novelization author Alan Dean Foster is. The books however can offer additional insights by stepping into the minds of the main characters, as well as offering untold details in the narrative, since most are based on earlier versions of the scripts, which often makes them an interesting addition to a film, all the while failing as a satisfying replacement.

That leaves comic book adaptations of films. The visual medium seems to be

perfectly apt to adapt films, and early in its history, comic strips would use

popular characters and actors from the big screen as the heroes of short

vignettes. Cartoon versions of Chaplin, Keaton, Cagney and their compatriots

would grace regularly the pages of the British magazine FILM FUN, which ran

from 1920 to 1962 with an amazing 2225 issues.

|

| Buster Keaton in a one page vignette from a 1928 issue of FILM FUN. |

While comics borrowed characters from the silver screen, they wouldn’t do literal adaptations of films until 1934 when another British magazine, FILM PICTURE STORIES, ran a series of adaptations of popular American movies of the time, allocating roughly 6 pages for each film, and transposing to ink roughly 120 flicks in its 30 issues run, before they merged with FILM FUN in 1935. What set this series apart was that it was one of the rare incursion in longer narrative storytelling in comic book form, which up to then, apart from the occasional adventure strips like TARZAN or DICK TRACY, usually maintained a one-page vignette format. 1934 would be a prime year to keep revolutionizing the format with the creation of such classic strips as Alex Raymond’s FLASH GORDON and Milton Caniff’s TERRY AND THE PIRATES which would redefine the genre.

|

| POLICE CAR 17, Probably the first extensive adaptation of a movie in comic book form, in the July 1934 issue of FILM PICTURE STORIES. |

In 1939, which was also an amazing year for movies, National Publications (The predecessor of DC Comics) published 6 issues of the aptly named MOVIE COMICS, which would feature comic strips set in the movie world (like Harry Lampert's MOVIETOWN), strips evoking movie storylines (like Ed Wheelan's MINUTE MOVIES), but mainly would focus on movie adaptations using photographs as a sprinboard for illustrations, creating this mutant artwork, half-fumetti, half traditional drawing. It covered a wide array of styles, from Western to horror, including comedies, serials and historical dramas. Each issue would feature between 5 to 6 movies, including SON OF FRANKENSTEIN, GUNGA DIN, STAGECOACH and THE MAN IN THE IRON MASK.

In the fifties, Fawcett Comics, well-known as the publishers of the original CAPTAIN MARVEL (aka SHAZAM for you youngsters out here), in the fifties dabbled also in comic book adaptations of movies with two series that focused mainly on Westerns (that were all the rage at the time). MOTION PICTURES COMICS ran for 14 issues or so in 1950, featuring films such as THE RED BADGE OF COURAGE, THE TEXAS RANGERS and WHEN WORLDS COLLIDE. FAWCETT MOVIE COMICS came out roughly at the same time and ran for about 20 issues, with movies like IVANHOE, THE OLD FRONTIER and THE MAN FROM PLANET X. The artwork was often top-notch, including work by the likes of Kurt Schaffenberger and Dick Rockwell.

|

| The last issue of MOVIE COMICS, with a feature on THE PHANTOM CREEPS, which incidentally has one of the coolest looking robot in movie history. |

|

| The last page of the SON OF FRANKENSTEIN adaptation in MOVIE COMICS # 1. |

In the fifties, Fawcett Comics, well-known as the publishers of the original CAPTAIN MARVEL (aka SHAZAM for you youngsters out here), in the fifties dabbled also in comic book adaptations of movies with two series that focused mainly on Westerns (that were all the rage at the time). MOTION PICTURES COMICS ran for 14 issues or so in 1950, featuring films such as THE RED BADGE OF COURAGE, THE TEXAS RANGERS and WHEN WORLDS COLLIDE. FAWCETT MOVIE COMICS came out roughly at the same time and ran for about 20 issues, with movies like IVANHOE, THE OLD FRONTIER and THE MAN FROM PLANET X. The artwork was often top-notch, including work by the likes of Kurt Schaffenberger and Dick Rockwell.

|

| FAWCETT MOVIE COMICS #15, featuring artwork from celebrated artist Kurt Schaffenberger. (Fawcett, 1952) |

And there there was Dell. Partnered

with Western Publishing since 1938, Dell Comics had made an habit of licensing

popular characters for their publications. Warner Bros cartoons, Disney or The

Lone Ranger, all silver screen heroes that got to experience new adventures in

comic book form. When the partnership ended in 1962, Western Publishing

launched Gold Key Comics, who turned out to be the grand licensing champion of

the sixties, having secured rights on a vast array popular films, like TWENTY

THOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA, KING KONG or FANTASTIC VOYAGE, just to name a few. However, the

competition from the resurgence and astounding popularity of Superheroes coming

from DC and Marvel eventually lead to their untimely demise in 1984. In a way,

licensing properties turned out to be their weakness, because it was impossible

for them to actually create licenses for their comic book characters to create

extra revenue, selling toys or other products plastered with the likeness of

their comics, like it was current practice for companies with original

characters like DC and Marvel, for instance. Gold Key did have a few original

characters, like DOCTOR SOLAR MAN OF THE ATOM, TUROK SON OF STONE or MAGNUS ROBOT FIGHTER, but most likely not popular

enough to license them out.

After taking over a bunch of Western properties from Fawcett comics in the mid fifties, featuring popular actors like TOM MIX and TEX RITTER, Charlton comics also kept busy grabbing movie licenses here and there in the sixties, like the one-shot MARCO POLO with terrific artwork by Sam Glanzman (based on the 1962 Pierro Pieroti/Hugo Fregonese film of the same name starring Rory Calhoun) or going the Photonovel way with an adaptation of the 1963 Robert Gordon film BLACK ZOO. This last magazine was pretty much a companion to their other magazines inspired by FAMOUS MONSTERS OF FILMLAND, MAD MONSTERS and HORROR MONSTERS.

|

| The Charlton adaptation of the 1962 movie MARCO POLO, with artwork by Sam Glanzman. (Rumor had it that editor Dick Giordano redrew some of the faces in the comic) |

Aware of the popularity of monsters, Charlton obtained the rights to a few monster movies to create new stories after the first issues focused on the actual adaptation of the original films. Featuring artwork by the legendary Steve Ditko (who also provided artwork for Marvel on their own monster comics, as well as creating with Stan Lee characters like Spider-Man and Dr. Strange) on key issues, Charlton published comics based on John Lemont's terrific 1961 film KONGA, and Eugène Lourie's amazing film from the same year, GORGO. Writer Joe Gill, inspired by the original scripts from the films, created a series of improbable adventures for the KING KONG and GODZILLA clones. Drinking buddy Ditko marvelled at Joe Gill's scripts in a 1992 interview: "I read the screenplay of Gorgo. From the first reading to this day, I

marvel at how well Joe adapted the character to comic books. I didn't

read the Konga screenplay but that comic script was (also) a treat" . In a move that recalls the evolution of GODZILLA in movies, both GORGO, KONGA, and later REPTILICUS (based on the 1961 Danish monster movie by Sidney Pink. Note: the comic book series ended up changing its name to REPTISAURUS) all went from destructive forces of nature to defenders of humankind in their respective series. However, not unlike Marvel's HULK, they are misunderstood by the very people they seek to protect. As Ditko strted to get more and more work from Marvel, his contributions to those comics ended up being a cover here and there, and the interior art was taken over by the team of Montes and Bache (A fascinating analysis of those series can be found here).

|

| Charlton reprinted some of Ditko's work on the first issues of KONGA and GORGO in 1966 in FANTASTIC GIANTS. |

DC Comics

also tried to dip their toes in movie adaptations with the first issue of their

anthology science-fiction series STRANGE ADVENTURES, with an adaptation of

DESTINATION MOON. They also published in issue 43 of DC Showcase a reprint of a British adaptation of DR. NO originally published in Classics Illustrated #158A in 1962. But their early forays in movie adaptations were few and far

between, focusing mainly on adapting occasionally one of the movies based on their own characters (Burton's BATMAN, SUPERMAN III, etc... ) They also took over the STAR TREK franchise from Marvel right after STAR TREK II. creating their own story lines with the aging crew of the Enterprise, adapting STAR TREK III along the way.

But it's really Marvel Comics who would take the baton of movie adaptations with gusto, as Gold Key were slowly ebbing away, when editor Roy Thomas grabbed the license for THE PLANET OF THE APES after the film series ended, and the TV series was starting in 1974. Doug Moench and Gerry Conway, assisted on artwork by George Tuska and Mike Ploog, among others, wrote 29 issues for a black and white magazine under the Curtis imprint. The main stories would be new adventures set on the simian world, and the backup would be adaptations of the original films. Part of those adaptations were reprinted in color in comic book format under the title ADVENTURES ON THE PLANET OF THE APES. Marvel wasn’t the first publisher to tackle the popular PLANET OF THE APES franchise. Gold Key had done their own version in 1970 of BENEATH THE PLANET OF THE APES, and the Japanese also made a manga version in 1971.

An amusing aside; Marvel was actually imposed a ''word limit per page'' in an attempt to avoid too much competitions with the novelizations that were being published at the same time. Somehow, in the licensee's mind, a story is told in words, so images do not count as storytelling in itself.

But it's really Marvel Comics who would take the baton of movie adaptations with gusto, as Gold Key were slowly ebbing away, when editor Roy Thomas grabbed the license for THE PLANET OF THE APES after the film series ended, and the TV series was starting in 1974. Doug Moench and Gerry Conway, assisted on artwork by George Tuska and Mike Ploog, among others, wrote 29 issues for a black and white magazine under the Curtis imprint. The main stories would be new adventures set on the simian world, and the backup would be adaptations of the original films. Part of those adaptations were reprinted in color in comic book format under the title ADVENTURES ON THE PLANET OF THE APES. Marvel wasn’t the first publisher to tackle the popular PLANET OF THE APES franchise. Gold Key had done their own version in 1970 of BENEATH THE PLANET OF THE APES, and the Japanese also made a manga version in 1971.

An amusing aside; Marvel was actually imposed a ''word limit per page'' in an attempt to avoid too much competitions with the novelizations that were being published at the same time. Somehow, in the licensee's mind, a story is told in words, so images do not count as storytelling in itself.

Licensing

fees can be rather expensive, yet Marvel persisted in other isolated attempts.

In 1975, it teamed up for the first time with its ‘’distinguished competition’’

DC Comics for an oversized adaptation of THE WIZARD OF OZ, predating by a year their celebrated collaboration SUPERMAN VS THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN.

The following year, Marvel hired legendary artist Jack Kirby to interpret Kubrick’s masterpiece 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY in a tabloid sized Marvel Treasury Special, which lead to a regular series of new stories by Kirby that were only loosely based on Arthur C. Clarke’s seminal novel, creating in the same breath his character MACHINE MAN who would go on to have his own series. In early 1977, they released an adaptation of the popular Science-fiction film LOGAN’S RUN, but it didn’t last longer than 6 issues. The last issue had the distinction of featuring a back-up story starring none other than the Mad Titan himself, Thanos.

The following year, Marvel hired legendary artist Jack Kirby to interpret Kubrick’s masterpiece 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY in a tabloid sized Marvel Treasury Special, which lead to a regular series of new stories by Kirby that were only loosely based on Arthur C. Clarke’s seminal novel, creating in the same breath his character MACHINE MAN who would go on to have his own series. In early 1977, they released an adaptation of the popular Science-fiction film LOGAN’S RUN, but it didn’t last longer than 6 issues. The last issue had the distinction of featuring a back-up story starring none other than the Mad Titan himself, Thanos.

|

| Jack Kirby's 1976 adaptation of Kubrick's science-fiction classic. After 6 years spent working for the competition at DC where he created notably THE NEW GODS, he came back to the company he helped put on the map in the sixties. When Marvel purchased the rights to 2001 from MGM, they knew right away they wanted Kirby on it. He was not as enthusiastic, weary of adapting from another person's story. When he was done, he stated that it was "an honor, but not a lot of fun." |

By 1977, the PLANET OF THE APES license was starting to run stale, so Roy Thomas convinced an ambivalent Stan Lee to give a chance to an unknown Science-Fiction movie called STAR WARS. Lee resisted, not believing in the sales potential of a science fiction license comic book, but he finally conceded.

The move

proved to be a fortuitous one as STAR WARS mania grasped the World by the throat, and

with the help of Charles Lippincott, George Lucas’ advertising publicity

supervisor, all things STAR WARS were selling like hot cakes. Marvel

comics at the time were struggling, plagued by declining sales, and the

astounding success of the STAR WARS comic book adaptation may just as well have

saved them from vanishing into the night. The series, which imagined new adventures with

Skywalker and friends, after the first 6 issues that adapted the movie itself,

continued for 9 years until issue 114. (Interestingly, original artist Howard Chaykin is particularly sour about that early work)

From that point on, licensed movies and Marvel comics were like peanut butter and jelly. They started a whole series of MARVEL MOVIE SPECIAL adapting movies like TIME BANDITS, KRULL, THE DEEP or ANNIE, and the magazine sized MARVEL SUPER SPECIAL that would print four color versions of, among others, CONAN THE BARBARIAN, OCTOPUSSY, 2010, or STAR TREK THE MOTION PICTURE.

Comic book adaptations of famous movies continue to this day, and many different publishers share a multitudes of licenses, often creating fun and unlikely team-ups, like KONG ON THE PLANET OF THE APES, or the now classic ALIENS VS PREDATOR, that went full circle and generated a pair of lackluster films from 20th Century Fox.

But as much

as comic books are a decent approximation of film language, in a pre-home video

world, it still didn’t quite translate the actual visuals with the most

accuracy. A talented yet mundane team

like Dave Cockrum and Klaus Janson were far from being able to convey Douglas

Trumbull’s sublime visual prowess from STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE.

Contrary to Marvel, who would rarely put their top talents

on movie adaptations (with some exceptions like Bill Sienkiewicz on

DUNE in 1985) Heavy Metal Magazine were instead interested in

‘’casting’’ interesting teams on their adaptations. Jim

Steranko delivered a stunning adaptation of Peter Hyams’ OUTLAND.

Archie Goodwin and Walter Simonson drafted a superb version of ALIEN.

And ‘’mundane’’ is the last word one would think while

perusing the unlikely pairing of Rick Veitch and Stephen Bissette’

s vision of Spielberg’s infamous 1941.

Four years after he would offer his unique vision of Spielberg's infamous bomb, Stephen Bissette took the comic book scene by storm by being part of the award winning team that revitalized the SWAMP THING, along with writer Alan Moore and co-artist John Tottleben.

BD- You did some work together for HEAVY METAL before the 1941 illustrated story?

Still, John Workman saw that story, in two variations, and he'd seen the collaboration with Rick on the artwork for the Ron Goulart short story adaptation of "Into the Shop" I'd done for Marvel's black-and-white magazine MARVEL PREVIEW PRESENTS STARLORD, and the horror comic story "Cell Food" we'd done for Cliff Neal's DR. WIRTHAM'S COMICS & STORIES, so he knew we did and could work together. Workman also would have seen the other work we'd done for DR. WIRTHAM'S, including our collaboration on "The Tell-Tale Fart" , and the work we'd done separately for DR. WIRTHAM'S, and for Larry Shell. I can't recall if Rick had shown Workman Rick's brilliant Will Elder-like parodies he'd done for Shell, "Nutpeas" and "Momma's Bwah" , but I think he had, so Workman knew Rick had the Kurtzman/Elder approach to satiric comics hard-wired into his own DNA. In any case, it was Workman who approached Rick and I as a potential team to work on HM's second movie-adaptation graphic novel—"The Illustrated Story"—of Steven Spielberg's forthcoming 1941.

BD- I believe Alex Toth was supposed to do the adaptation. Why was he replaced?

BD- Why do you believe you were chosen to replace him? One doesn't look at Toth's style and say; ''Bissette and Veitch are pretty much the same.''

BD -What do you have to work with for a movie like this? Script. Photos?...

SB- Here's what we had, both essentially stolen for us by Heavy Metal art director John Workman:

BD- Any complications during the process?

SB- Oh, Christ, yes. Of course. I'll be brief, but look, I was the major complication. It pretty much broke Rick's and my collaborative relationship, doing 1941, and that's all on me. Rick's a workhorse, never misses a deadline, never has missed a deadline, never will miss a deadline. Me, I'm terrible with deadlines, always have been, always will be. As Rick wrote on my gravestone on the final page of Saga of the Swamp Thing #50, "late for his own funeral."

In short, moving back to Vermont to work together on the graphic novel was both a brilliant idea and a horrible terrible stupid idea. I was aching to get back to my home state; I'd had it with New Jersey, and was absolutely miserable living in and around Dover NJ after having graduated from the Kubert School. I longed for Vermont: the fields, the woods, the isolation, the wilderness. Had I stayed in NJ, in my little room with one bed, one drawing board, and only what was left of my comics and record collection, there would have been nothing to do except work on the 1941 pages. I still would have driven Rick nuts, no doubt, and fucked up and all, but moving back to Vermont was both the best and worst idea. Rick found a one-room brick schoolhouse for rent on Fisher Hill Road in Grafton, VT—no electricity, no running water (a four-hole shithouse extension in the back, dating back to the 1860s when the place was built)—and that's where I lived for the next couple of years. $60 US a month, can you believe it? It's still there, in much better shape than it was when I moved in, in part because of my having installed electricity while renting the place—that's a whole story in and of itself, which I won't go into here.

Rick already had a place on the other end of Grafton, a two-room shack with kitchenette area and an outhouse. Neither of us had a car, we bicycled our pages to and from one another's place. And so we got to work, having completed our 'audition' pages and what became the endpapers while still in New Jersey, then having landed the gig, I moved to this one-room schoolhouse in Grafton, summer of 1979. And it was a glorious summer, and I missed Vermont so much, and I would just... disappear into the woods, go hiking, eat mushrooms and go tripping, etc. My landlords, Theron and Iva Fisher, had a really sweet farm dog named Banjo, a husky mix with thick gray-and-white fur and a really friendly disposition, and Banjo would come to visit me at the schoolhouse, and I'd drop everything and go for a hike with Banjo (never having had a dog in my life, it was the next-best thing: being pals with my landlord's dog). Instead of doing the job, working on the pages. Oh, I'd work on 'em, fits and starts, bursts of activity, then I'd vanish for days at a time, reconnecting with the wilderness, and you can imagine how absolutely unprofessional and maddening this was for Rick, who was older and wiser and far more disciplined than I was.

Of course, it also didn't help that there was no electricity in my place—I had two car batteries I'd hook my drawing table lamp and record player up to, and work until the juice ran out about 1 AM or so, and then have to go to bed because you can't draw or paint by candlelight—and I couldn't afford the installation cost of getting the schoolhouse wired for electricity until later that summer. That was a constant problem, but really, I was the problem. I was so intoxicated with being back in Vermont that I'd just piss away a day or five fucking about and exploring the woods and so on.

I still have somewhere in my files an ink drawing Rick tacked to my door that I came home to one twilight after wandering afield since dawn. He'd biked in four more pages to find me gone and no pages for him to pick up, and he sketched himself holding scrawny stinky (no shower) me by the neck, smashing my face with a flat iron, with spatters of real blood on my face, and a caption: "Better get yourself a new partner, Bissette." That got me back in line—for a bit.

There were other complications. Allan Asherman flaked on the script pages, as I'd mentioned. I have no idea or recollection what was going on with Allan, but he flaked worse than I'd flaked, and in the end Rick scripted and lettered right onto the boards the final stretches of the adaptation, sans script pages from Asherman. We also converted some sections we'd planned to draw in minute detail into collage gags instead, but since that was the 'look' and kinetics we'd set up from the beginning—that's what had gotten us the job, really—shifting gear to collage to get certain pages done worked just fine. I had a whole aesthetic around using collage for my comics work at that time, and we ramped that up to the nth degree for 1941. This included using organic matter as collage material—actual eggshells pasted down in some panels, even a bit of blueberry yogurt for the proper purple/blue on one page—and no page was completed until I'd applied my patented 'sweat' droplets, something I'd refined from how Spain Rodriguez drew beads of sweat into a more painterly, very tactile rendition of sweat droplets.

BD -And Spielberg ended up writing a letter to the editor complaining about the end result (all the while giving props to the artists. How did this make you feel?

SB- Well, that was funny. It was both a badge of honor and a last kiss-off, wasn't it?

Truth to tell, so many of our creative decisions had been fueled by our frustration with how uncooperative Spielberg and the studio people were. We did all that work in a vacuum; we didn't even have an editor, really, John Workman was the only meaningful contact we had with anyone at Heavy Metal, so John was both our editor and our audience. John loved what we'd done, and told us so repeatedly. But the movie people just kept tying our hands: that whole crazy thing with having to steal reference materials, the script. We were under contract to do the job with them, for them, and we were treated like the mutant relative you shut up into the basement or attic, so fuck 'em. That fed the maniacal ire we poured into the adaptation.

I remember looking forward to drawing Toshiro Mifune and Christopher Lee as the Japanese sub commander and meddling German officer, only to be told early on that we couldn't use Mifune's likeness—as it was explained to us at the time by John Workman, Mifune had it in his contract that his likeness could not be used in any way to promote the film. So, being denied the honorable route of delineating one of my personal cinema heroes who was actually in the movie, Rick and I decided, fuck it, we'd embrace the rampant xenophobia we found all over that year of Life magazines from 1941 and we'd go the route of parodying such racism by caricaturing the Japanese in the ways they were hideously caricatured in the animated cartoons, comic books, and anti-Axis propaganda of 1941 and WWII. We embraced it and made it essential to our Kurtzman/Elder approach to the whole adaptation.

|

| The stunning original artwork by Walter Simonson for Heavy Metal's version of ALIEN. |

|

| A page from Bill Sienkiewicz' stunning artwork from Marvel's adapatation of David Lynch's DUNE in 1985. |

Four years after he would offer his unique vision of Spielberg's infamous bomb, Stephen Bissette took the comic book scene by storm by being part of the award winning team that revitalized the SWAMP THING, along with writer Alan Moore and co-artist John Tottleben.

Born in 1955, Bissette is a proud Vermonter, and just retired in 2020 from teaching at the Center for Cartoon Studies. But he keeps writing about genre cinema (and as a matter of fact just published a 660 pages book dissecting Cronenberg's THE BROOD), sketching and sharing his views daily on social media platforms.

I had the opportunity to talk to artist Stephen Bissette about his experience on 1941: The Illustrated Story.

We

did all kinds of odd comics jobs for Joe after-hours as a result.

Heroes World ad pages and catalogues (now revered by some collectors),

reformatting photostats of Golden Age and Silver Age DC comics art

pages for those mid-1970s smaller, standard-paperback-size New

American Library DC collections, more elaborate reformatting of stats

of vintage DC stories/art for some massive educational publisher's

package of comics-as-learning-tools (i.e., re-lettering every caption

and balloon into the approved, grammatically proper new text; changing

artwork to reformat the page dimensions and to censor or alter

'objectionable' elements into the new educator-approved images,

etc.), public service and/or industry comics , and even PS MAINTENANCE MONTHLY pages, once Joe

had that contract from the military... etc. etc. etc.

I had the opportunity to talk to artist Stephen Bissette about his experience on 1941: The Illustrated Story.

BD- You first met Rick Veitch at the Joe Kubert school. This is where you started

working together?

SB- Yep,

Rick Veitch was one of the first classmates I met at the Joe Kubert

School, that would have been very late August/very early September,

1976. Rick was one of my heroes, and the reason I even dared apply to

attend the Joe Kubert School, when a lot of others in my

life—including my then-mentor and primary art instructor at Johnson

State College in Johnson, VT, which I'd been studying at for two

years up to that point—were discouraging me to even think about

going. I'd been inspired by the underground comix, buying and reading

every one of 'em I could lay hands on, TWO-FISTED ZOMBIES (Rick's

collaboration with his brother Tom, for Last Gasp) among them.

Somewhere I'd read Rick and Tom were from Bellows Falls, Vermont; I

knew from growing up in Vermont where Bellows Falls was, and what

kind of town it was. I was a scrawny kid from Duxbury and Colbyville,

Vermont: what hope did I have to carve out any path making comics?

Knowing Rick and Tom were already published and doing so, coming from

sketchy ol' Bellows Falls—well, it meant maybe I could, too. So

even before we met, I owed a huge debt of gratitude to Rick.

|

| Original artwork by Rick and Tom Veitch for TWO-FISTED ZOMBIES #1 (Last Gasp, 1973) |

So,

yes, we also started working together from time-to-time there, too.

That relationship grew pretty organically, and I think we each

brought something the other could work with and off of to that

growing relationship. I was much younger—I was 21 and on my own

when we met, Rick already had a wife and son—but I was steeped in

cinema and certain genre forms (literature, comics, movies) and had a

passionate impulse about the how-and-whys of storytelling that was

off the beaten track. I was into storytelling in a different way than

Rick was, or any of our classmates, really. It was weird, I was

weird, but we sure meshed on the pages once we started tinkering

around with what we might want to and/or be able to do together.

BD- And

Joe Kubert offered you your first crack at big time.?

SB- Ha!

Define "big time."

Well,

yes, he did; Joe and Muriel Kubert had a 'work' program at the Kubert

School. If you were on top of your assignments for class, you could

work after-hours on paying gigs. Low pay, but pay, nonetheless.

|

| One of the many catalogues Kubert school students would contribute their blooming talents to. |

Rick also became Joe's

right-hand-man on some self-standing projects I remember—a huge project for World

Color, the primary American printer of four-color comics at that

time, detailing how comics were produced and printed—in part

because Rick was the most trustworthy of all of us, the most

dependable; in part because Rick had worked out something special

with Joe and Muriel to afford attending the school. But Rick was by

far the most reliable freelancer of everyone in that first class: he

made all his deadlines. He did terrific work. And Joe understandably

came to depend upon Rick.

A

few of us had shots at doing either "Battle Albums," gag

pages, or drawing backup stories (usually 2-to-6 pages in length) for

SGT. ROCK, the DC Comic Joe was editor on. Rick Veitch, Tom Yeates,

Ron Zalme, and I really jumped on those when it was possible, and

nobody did more of that work for Joe than Rick Veitch. Rick and I

jammed on our first SGT. ROCK story together: "A Song for Saigon

Sally" , a really organic collaboration on every page, with the

advantage of Joe overseeing and correcting all our layouts and

pencils before we inked the final pages. That one was a steep

learning curve, for sure.

So, that turned out to be my closest brush with what later was "the big time"—for Bob Stine, that is.

SB- Well,

there was no one method for us—there were many variables, including

my own distractions and lack of discipline—but let me see if I can

address this properly.

|

| A page from the Bissette/Veitch collaboration ''A song for Saigon Sally'' in Sgt Rock #311. (DC Comics, 1977) |

By

the time I tackled my next SGT. ROCK opportunity, my brush-and-ink

skills had come along a long ways in a relatively short time. I

solo-penciled-and-inked a Robert Kanigher WWI sniper script/story,

and a pretty bizarre "Battle Album" on animals used in

warfare, but the breakthrough for me was being allowed to script a

backup story for my classmate Tom Yeates—"Live by the Sword,

Die by the Sword"—and eventually script-and-pencil-and-ink my

own solo SGT. ROCK backup story, "Crabs!" That's a really

critical arc of work in my development as a cartoonist and creator,

and it all was done for and published in SGT. ROCK.

|

| The artist is finding his voice. Stephen Bissette writes, pencils and inks his own backup story in SGT ROCK 343 (DC Comics, 1980) |

What

felt like a shot at "the big time" was Joe's extraordinary

invitation to me to contributed something original to SOJOURN, this

massive creator-owned comics tabloid Joe had conceived and would be

editing and co-publishing (Ivan Snyder, Heroes World, was the

co-publisher partner). Joe saw some potential in me nobody else did,

and asked me to come up with an ongoing poster series that would be

narrative in nature: each poster spread (full color) would be part of

a narrative continuity, a story. With my usual skewed commercial

instincts, I proposed "Kingdom of the Maggot" , a sort of

feral Robert E. Howard/Tolkienesque fantasy involving these sort of

Sasquatch-like bestial hunters. Joe loved it, and cut me loose. I

delivered two posters that saw print in SOJOURN #1 and 2, but as I

was inking the third, Joe informed me the project was terminated:

SOJOURN was no more. So much for "the big time," Eric.

|

| Stephen Bissette's artwork for SOJOURN's ''Kingdom of the Maggot''. |

Turned

out the most vital freelance gig I completed for and working with Joe

Kubert was a modest three-page story for Scholastic Magazines, "The

Villager's Victory" scripted by Scholastic editors Bob and Jane

Stine for a new Scholastic magazine to be distributed into schools

called WEIRD WORLDS. It was a STAR WARS-era sf/monster magazine for

school kids, Middle Grades and up, I reckon. My name wouldn't be on

the story—it was to be credited to the Joe Kubert School, and I

understood and was fine with that—but Joe wanted me to take the job

seriously and not draw 'down' to a younger readership, but to draw it

as I would a horror story of my own. It was a werewolf story, and Joe

rode me hard on the layouts and pencils, then trusted me to cut loose

on the inks on my own, and both Joe and the Stines were overjoyed

with what I delivered. I really gave it my all: it felt like

retribution of a kind, drawing a horror comic story for school

readerships, whereas when I was a kid in school in the 1960s, my

comics were taken away from me! Payback, you see. So I gave it my

all.

|

| Bissette's gorgeously gruesome artwork for WEIRD WORLDS (Scholastic, 1978) |

Well,

I got to do more, and Joe and Scholastic let me sign my own name to

the next job, and when I graduated in spring 1978, Joe 'gifted' me

that freelance contract to continue working with Bob and Jane and the

good folks at Scholastic. That was vital: it was a fun series of

gigs, Scholastic paid the best page rates I'd ever imagined, the art

director Bob Feldgus was also a great guy and made working with them

all a pleasure, and the print quality was superior to what any other

comics publisher of the time (including HEAVY METAL) seemed capable

of. I ended up doing a series of stories with/for Scholastic,

including fully-painted black-and-white and one color story. Bob

Stine, BTW, became better known later as R.L. Stine, creator and

author of the GOOSEBUMPS books series that spawned TV series, movies,

etc.

So, that turned out to be my closest brush with what later was "the big time"—for Bob Stine, that is.

BD- What

is your work process as a team?

There

were three methodologies, if I had to break it down in retrospect:

*

The job-jobs, the work we did as part of the work programs, we tended

to just tackle in the classroom studio, where all the students had

their own tables. First year, fall 1976-summer 1977, there was just

the pioneer class that Rick and I were part of, along with classmates

like Tom Yeates, Ben Ruiz, Ron Zalme, Sam Kujava, Cara

Sherman-Tereno, Rick Taylor, and so on—there were, I think, 17 of

us from the get-go. Only so many of us were part of the work program,

either because we were qualified and interested, or because we were

just willing to tackle the work, which was often production-oriented

(lots of paste-ups and mechanical work, with touch ups and some

redrawing on slick photostat paper materials). I could go into detail

if you wish, but trust me, it wasn't particularly romantic work,

though it did prep Rick and I for aspects of our collage components

on the later '1941' job for Heavy Metal.

Joe

supervised all this work, and that first year in particular he was

intensively, steadily 'hands on.' His own studio that first year was

right across the front hallway from our classroom studio space, so it

was ideal in a lot of ways: Joe would walk us through the tasks at

hand, and we would go to-and-from his studio space as necessary for

input, corrections, etc. Nothing but nothing was done until Joe

approved it, and as I say, it was really 'hands on'—Joe would slap

tracing paper over something and draw precisely what he wanted, or if

you were further along and still a bit 'off' rework it right on your

own pencils, or on the mechanics. He often would either make

corrections himself, re-inking or so on, having a solid grasp of what

each of us was or would be capable of doing. If you nailed it, the

praise wasn't effusive: you were handed the next page or task at

hand, which we all knew meant Joe was satisfied, or knew you'd taken

it as far as you could, but still trusted you could tackle the next

page or ad or whatever. If your work wasn't up to snuff, and Joe

accepted it to fix it himself, you knew where you stood based on

whether you were handed more work to do, or thanked and not asked to

do more.

It

was a real studio system in that regard, and it was Joe's studio, no

two ways about it. He was the man, and if the work wasn't up to Joe's

standards, he put his hand to it to ensure it was up to his standards

of completion.

*

The work gigs that were jobs for Joe, but we had more autonomy

with—assigned comics jobs like the Sparky the Firedog comic, the

World Color comic, the assigned SGT. ROCK backup stories from

existing scripts Joe had already edited to be penciled—those were a

completely different thing, with a completely different process. When

we were just starting out, Joe would ask to see thumbnails, page

roughs, complete: we were to break down the entire story while

adhering strictly to the edited script. Joe would then go over every

single panel, page, word balloon and caption placement, reworking

your thumbnails with you—sometimes putting his pencil to tracing

paper to show you better ways of doing something—or, if he wasn't

satisfied, he'd ask you start over completely.

Since

Rick and I started out working together on "Song for Saigon

Sally," as a team, we worked up thumbnails in our sketchbooks

over in our dorm rooms (in the Carriage House, across the way from

the Baker Mansion classroom building), then transfer those to typing

paper in pencil form to deliver to Joe. That first story we laid out

together, working very closely, and I can't recall how many stages we

might have had to go through. Having grown up reading Joe's work, I

think it's fair to say Rick and I had a pretty good grasp as readers

as to how we thought Joe might lay out the story, and we tried to

work to that level: page layout, use of inset panels, sound effects,

and so on. My recall is Joe reworked something on every page,

sometimes extensively, but he wanted to see what we could do, what

our work would look like: he wasn't looking for us to 'clone' Joe's

style. But he was the master, if you will: our editor, our mentor,

and we wanted to please Joe, and we sure wanted to do the best job we

could. We also collaborated on a back-up story involving the French

Resistance and a spy, that for some reason I can't recollect turned

out to be a real patchwork job; I think it was a super-tight deadline

or something, so Rick and I did the story with Joe really jumping in

big-time. Rick may remember, it was a story with a final line of

dialogue ("Marteau was—A WOMAN!") we laughed about and

used to reference whenever we needed to crack each other up.

|

| ''Marteau...was a woman!'' Last page of the back-up story THE SNITCH from SGT. ROCK #335 (DC Comics, December 1979). Art by Rick Veitch, Stephen Bissette and Joe Kubert. |

When

we weren't working together on something for Joe, it was quite

different. If it was assigned work—drawing from a script, which I

did at least two more of (a WWI sniper story from a Bob Kanigher

script, and a WW2 German tank-in-the-desert story) and Rick did a lot

more of (scripts by Kanigher, Bill Kelley, etc.)—the method I

described above was pretty much how it went, only individually. Rick

did more backup stories for ROCK than any of us, of that I'm

absolutely certain.

If

it was a story or Battle Album we cooked up and were hoping Joe would

go for, it was another kettle of fish altogether. We'd individually

'pitch' our ideas to Joe for stories or Battle Albums, usually all

laid out and scripted in some form or other; again, Rick did more of

that than any of us, including some science-fiction war stories that

anticipated the kind of stories Rick later did for Archie Goodwin for

Epic Illustrated. I pitched a number of stories to Joe, but he only

went for a couple of them—the story I mentioned earlier that I

scripted for Tom Yeates, tailored to Tom's interests as best I could,

and "Crabs," the only 'War That Time Forgot'-type story I

ever sold Joe on while I was living in Dover NJ attending the

school—but once Joe went for a pitch, he pretty much left me alone

to just see it through after we tightened up the layouts and my

pencils were satisfactory. My recall is Joe worked Rick much, much

harder than he did me, for whatever reasons, but as I say, Rick also

did a lot more of that work for and with Joe than I did.

This

method was what Joe had me use on my first Scholastic story for Bob

and Jane Stine (editors and writers), but for that one Joe really let

me cut loose. It wasn't signed with my name—it was signed with the

Joe Kubert School tag—but Joe let me do the whole thing, except for

the lettering (my lettering sucked and still sucks; Rick's was and is

excellent): layouts, pencils, inks, toning (I did it on DuoShade

paper, a two-toned chemical-sensitive board). He was really pleased

with it, and let me do the next story on my own, and sign it, and

when I graduated Joe gifted me that contract, which was a real

blessing for a freelancer just starting out, and a real vote of

confidence from Joe.

But

if it was our own material that Rick and I were doing, it was more

like playing jazz or something. We loved brainstorming together, we'd

really bounce around ideas and it was more like play than work until

you got to the point where the pages just had to be finished,

do-or-die. We evolved our own method of collaborating that served us

pretty well.

BD- You did some work together for HEAVY METAL before the 1941 illustrated story?

SB- Well, no, I don't recall Rick and I collaborating on anything in the page of HEAVY METAL, but I was in HM early on. We tried, Rick and I, unsuccessfully, to turn an original 'jam' color piece HM art director John Workman was really taken with—a painting Rick and I had concocted of giant sea monkeys, our science-fantasy literalization of the 'sea monkeys' in the comic book ads—but John didn't go for our story idea. We tried another approach, and the resulting story "Monkey See" was published in the second issue of HM's Marvel competitor, EPIC ILLUSTRATED.

|

| “Monkey See” from Epic Illustrated Vol. 1, #2 (Summer 1980) ©1980 Steve Bissette & Rick Veitch |

If

you dig into the back issues of HEAVY METAL, you'll see I was among

the first American freelancers to show up in its pages, though

Richard Corben of course beat us all to the punch thanks to his

self-published-in-the-US classic DEN being serialized in METAL

HURLANT, the original Humanoides Associés publication that spawned

HEAVY METAL. When I arrived at Kubert School in the fall of 1976, I

had a then-complete set of METAL HURLANT, a gift from one of my

Johnson State College friends (Jack Venooker), and I turned Rick and

my classmates at Kubert School onto METAL HURLANT. When the first ad

and preview appeared in NATIONAL LAMPOON for their forthcoming new

publication HEAVY METAL, I almost immediately scheduled an

appointment with the new magazine's art director, John Workman. John

liked what he saw in my portfolio, and asked me to come up with some

one-page self-standing pieces. He bought two, both of which saw print

in 1977, and eventually bought an original story from me which ran in

HM entitled "Curious Thing," a sort of antic interstellar

Lewis-Carroll-by-way-of-Tex-Avery oddity that made visual sense—it

flowed like crazy—but no literal or true narrative sense. John was

very happy with it!

|

| One of Stephen Bissette's stories published in HEAVY METAL Magazine (and reprinted in 1985 in BEDLAM! #1) HEAVY METAL #19, October 1978 |

In

the meanwhile, it was our duty to one another to get one another into

any doors we'd managed to open as freelancers, so in short order John

Workman indulged meetings with Rick Veitch, John Totleben, and other

classmates. Workman loved John Totleben's work, but I think Workman

ended up only buying a single painted piece from Totleben for HM;

Rick had more luck, eventually doing his color "L'il Tiny

Comics" poetry-comic which was published in HM. But Rick and I

never collaborated on anything for HM, outside of that first draft of

what became "Monkey See" , which ran in EPIC ILLUSTRATED,

not HM.

|

| A page from Bissette and Veitch's collaboration for DR. WIRTHAM'S COMICS AND STORIES (March 1979) |

Still, John Workman saw that story, in two variations, and he'd seen the collaboration with Rick on the artwork for the Ron Goulart short story adaptation of "Into the Shop" I'd done for Marvel's black-and-white magazine MARVEL PREVIEW PRESENTS STARLORD, and the horror comic story "Cell Food" we'd done for Cliff Neal's DR. WIRTHAM'S COMICS & STORIES, so he knew we did and could work together. Workman also would have seen the other work we'd done for DR. WIRTHAM'S, including our collaboration on "The Tell-Tale Fart" , and the work we'd done separately for DR. WIRTHAM'S, and for Larry Shell. I can't recall if Rick had shown Workman Rick's brilliant Will Elder-like parodies he'd done for Shell, "Nutpeas" and "Momma's Bwah" , but I think he had, so Workman knew Rick had the Kurtzman/Elder approach to satiric comics hard-wired into his own DNA. In any case, it was Workman who approached Rick and I as a potential team to work on HM's second movie-adaptation graphic novel—"The Illustrated Story"—of Steven Spielberg's forthcoming 1941.

|

| “Momma’s Bwah” © 1980 Bill Kelley & Rick Veitch ~ Art by Veitch. (Published in Larry Shell’s ’50’s Funnies). Weird Dick © 1976 Rick Grimes. |

BD- I believe Alex Toth was supposed to do the adaptation. Why was he replaced?

SB- No

idea; we were only told at one point early on that Toth had been

their first choice, and it didn't work out, but we weren't told how

or why that hadn't panned out. In hindsight, I've read different

accounts about what had happened, but none that I can relate as

anything but hearsay; you'd have to talk to John Workman, unless Rick

can remember the specifics.

(Rick

Veitch's recollections aren't that more precise; reached to comment

on Alex Toth's refusal to work on the adaptation, this is what he

recalled. ''All I have is a very vague memory of Julie Simmons being

dumbfounded as to why he quit. She told us she had phoned Alex

thinking he was on board and he said "I don't want to talk to

you people." )

BD- Why do you believe you were chosen to replace him? One doesn't look at Toth's style and say; ''Bissette and Veitch are pretty much the same.''

SB- You've

got that fucking right! Having lost Toth, they didn't want a

surrogate Toth. I'm pretty certain John Workman, having seen our

portfolios, had seen "The Tell-Tale Fart" , knew what Rick

and I were capable of if we were cut loose, and I'm reasonably sure

Workman had seen and loved Rick's Kurtzman/Elderesque "Momma's

Bwah". Given what I know Workman had seen of my work, and of

Rick's and my work, I think he imagined a fusion of our sea monkey

painting (what became "Monkey See") and the MAD-like vibe

in "The Tell-Tale Fart" and even more evident and explosive

in "Momma's Bwah."

I

do recall it was made abundantly clear to us by John Workman that

since they couldn't get Toth, the idea was to take a completely

different approach to 1941—something quite other than, apart from,

what Toth might have done—and John thought Rick and I had "the

Right Stuff," so to speak. Workman wanted what Rick and I could

bring to the project, he didn't want us trying to emulate Toth's

work. Workman wanted our craziest stuff, and once we were contracted,

we went to work and pulled out all the stops, which Workman

consistently endorsed and encouraged throughout the process. We could

see HM editor Julie Simmons wasn't as comfortable with what we were

turning out, but Workman absolutely loved it. He'd laugh and chuckle

over pages as we delivered them.

|

| A page from Bissette and Veitch's adaptation of Spielberg''s 1941. ''Bestial and cannibalistic'' would the director say about the book. Where did he get that idea? |

BD -What do you have to work with for a movie like this? Script. Photos?...

SB- Here's what we had, both essentially stolen for us by Heavy Metal art director John Workman:

(1)

The shooting script of the movie; unsure which draft, or what stage

it was at, but it's all we had.

(2)

Black-and-white photostats hastily taken by John's staff on whatever

photostat camera or setup John had at Heavy Metal.

That's

what Rick and I had provided to us to work from. Period. Now, to

explain this, I'll jump into your next question, "And a certain

level of secrecy is required, I assume," because that "certain

level of secrecy" was what forced John Workman's hand in

acquiring for us (1) and (2).

My

recall is that Rick and I were called into NYC to the HM/National

Lampoon offices to meet a suit from the Universal Studios/Columbia

land-of-suits, who had it in his head that somehow Rick and I could

sit down with sketchbooks, watch a slide show of the "top

secret" slide images he had of the cast in costume and shots of

sequences that had been filmed or staged or mocked-up for photos, and

do sketches we could then use as reference to draw/paint the entire

graphic novel. I kid you not. That is, of course, insane: we needed

reference to work from for the duration of the process of drawing and

painting the graphic novel, and we sure as hell couldn't just "do

sketches" from a single rushed high-security sit-down that would

serve any purpose other than "oh, ya, that's Dan Ackroyd's

character" or whatever.

|

| Some of the lobby cards for 1941, most likely similar to the promotional material shown to Stephen Bissette and Rick Veitch during the infamous meeting at the National Lampoon offices in New York. |

We,

of course, initially thought the slides were for us to take with us,

as reference to do the graphic novel over the next couple of months

or whatever time we had. No, no, the suit was aghast: "you two

will walk down the street with these and sell them to Time magazine,"

he said at one point. We weren't to be trusted with anything, it

turned out: not a script, not a single photograph. Somehow, John

Workman talked the suit into going out and having lunch and he'd sit

us boys down and we'd do what needed to be done in the suit's

delusional mind, and off he went. John rushed the slides into the

stat room and Rick and I secretly went back to Vermont with

black-and-white photostats of the images (color would have been

either impossible or prohibitively expensive, and oh man we'd wished

we'd had color images more times than I can tell you). I don't

remember having to play along with a post-lunch session with the suit

from Universal/Columbia, so I think we just hustled out of the office

before he was back, and John dealt with whatever followed. Anyway,

the suit went home with the slides, thinking we'd done our sketches,

and Rick and I took the bus back to either Dover (where we still

shared rooms in the house with Tom Yeates and John Totleben) or to

Vermont, or to Dover en route to Vermont.

Can't

remember now if we left that visit with the script as well, or if

that came earlier, or came later, but eventually that script

became essential as Asherman fell behind on the scripting duties, and

Rick and I were doing finished pages without Asherman's script pages,

working directly from our layouts with Rick lettering right on the

boards from his own adaptation/compression of the movie's shooting

script. It became a real crunch, inevitably, and having that damned

script was all that allowed us to finish the work.

| One of the issues of LIFE Magazine that Bissette and Veitch used as reference material for the 1941 movie adaptation. |

Other

than art supplies (Dr. Martin's Dyes, Craypas, cattle markers—now

sold as "MeanStreak" sticks—colored pencils, and a

shitload of Bristol Board that we pre-cut to size, plastic bottles of

Higgins Black Magic ink, watercolor brushes, and nibs), our other

primary tools was a complete or near-complete set of Life magazines

from the year 1941. There was a used bookshop or antique shop in

Morristown, NJ that we knew of from prior visits that had an enormous

collection of back issues of Life stacked on this huge set of

formidable wooden shelving units; they were organized by year,

handily enough, and they were cheap. Cheap enough that Rick and I

borrowed John Totleben's car, or John drove us, and we purchased the

entire set from the year of 1941, figuring that any images—including

the vintage 1941 advertising art we were intent upon riffing with,

Harvey Kurtzman/Will Elder-style—would be appropriate to the

December 1941 setting of the movie we were adapting into comics form.

I cannot recall how in hell we got that monster stack of mouldering

oversized magazines back to Vermont, but we did, and half of 'em were

in Rick's Grafton VT living space/studio, and half of 'em were in my

Grafton VT living space/studio, and those were absolutely essential

raw materials for the collage methodology we applied to each and

every panel and page.

We

each also sacrificed the occasional clipped photo from a beloved book

or reference volume to serve a panel or page's needs as we pulled the

pages together. I still have copies of a glorious oversized

spiral-bound photo book on war movies I'd purchased at Marlboro Books

(which was this blow-out bargain bookshop in the Times Square area at

the time, a real haven for finding great books at stunningly cheap

prices) with pages and photos clipped out of it, and I still regret

having clipped an image or two out of my copy of Denis Gifford's A

Pictorial History of Horror Movies hardcover, but, hey, anything for

the art, right?

SB- Oh, Christ, yes. Of course. I'll be brief, but look, I was the major complication. It pretty much broke Rick's and my collaborative relationship, doing 1941, and that's all on me. Rick's a workhorse, never misses a deadline, never has missed a deadline, never will miss a deadline. Me, I'm terrible with deadlines, always have been, always will be. As Rick wrote on my gravestone on the final page of Saga of the Swamp Thing #50, "late for his own funeral."

|

| Last page from SAGA OF THE SWAMP THING #50 (DC Comics, 1982) where Rick Veitch comments on Stephen Bissette's chronic tardiness. (See tombstone on the bottom left) |

In short, moving back to Vermont to work together on the graphic novel was both a brilliant idea and a horrible terrible stupid idea. I was aching to get back to my home state; I'd had it with New Jersey, and was absolutely miserable living in and around Dover NJ after having graduated from the Kubert School. I longed for Vermont: the fields, the woods, the isolation, the wilderness. Had I stayed in NJ, in my little room with one bed, one drawing board, and only what was left of my comics and record collection, there would have been nothing to do except work on the 1941 pages. I still would have driven Rick nuts, no doubt, and fucked up and all, but moving back to Vermont was both the best and worst idea. Rick found a one-room brick schoolhouse for rent on Fisher Hill Road in Grafton, VT—no electricity, no running water (a four-hole shithouse extension in the back, dating back to the 1860s when the place was built)—and that's where I lived for the next couple of years. $60 US a month, can you believe it? It's still there, in much better shape than it was when I moved in, in part because of my having installed electricity while renting the place—that's a whole story in and of itself, which I won't go into here.

Rick already had a place on the other end of Grafton, a two-room shack with kitchenette area and an outhouse. Neither of us had a car, we bicycled our pages to and from one another's place. And so we got to work, having completed our 'audition' pages and what became the endpapers while still in New Jersey, then having landed the gig, I moved to this one-room schoolhouse in Grafton, summer of 1979. And it was a glorious summer, and I missed Vermont so much, and I would just... disappear into the woods, go hiking, eat mushrooms and go tripping, etc. My landlords, Theron and Iva Fisher, had a really sweet farm dog named Banjo, a husky mix with thick gray-and-white fur and a really friendly disposition, and Banjo would come to visit me at the schoolhouse, and I'd drop everything and go for a hike with Banjo (never having had a dog in my life, it was the next-best thing: being pals with my landlord's dog). Instead of doing the job, working on the pages. Oh, I'd work on 'em, fits and starts, bursts of activity, then I'd vanish for days at a time, reconnecting with the wilderness, and you can imagine how absolutely unprofessional and maddening this was for Rick, who was older and wiser and far more disciplined than I was.

Of course, it also didn't help that there was no electricity in my place—I had two car batteries I'd hook my drawing table lamp and record player up to, and work until the juice ran out about 1 AM or so, and then have to go to bed because you can't draw or paint by candlelight—and I couldn't afford the installation cost of getting the schoolhouse wired for electricity until later that summer. That was a constant problem, but really, I was the problem. I was so intoxicated with being back in Vermont that I'd just piss away a day or five fucking about and exploring the woods and so on.

I still have somewhere in my files an ink drawing Rick tacked to my door that I came home to one twilight after wandering afield since dawn. He'd biked in four more pages to find me gone and no pages for him to pick up, and he sketched himself holding scrawny stinky (no shower) me by the neck, smashing my face with a flat iron, with spatters of real blood on my face, and a caption: "Better get yourself a new partner, Bissette." That got me back in line—for a bit.

There were other complications. Allan Asherman flaked on the script pages, as I'd mentioned. I have no idea or recollection what was going on with Allan, but he flaked worse than I'd flaked, and in the end Rick scripted and lettered right onto the boards the final stretches of the adaptation, sans script pages from Asherman. We also converted some sections we'd planned to draw in minute detail into collage gags instead, but since that was the 'look' and kinetics we'd set up from the beginning—that's what had gotten us the job, really—shifting gear to collage to get certain pages done worked just fine. I had a whole aesthetic around using collage for my comics work at that time, and we ramped that up to the nth degree for 1941. This included using organic matter as collage material—actual eggshells pasted down in some panels, even a bit of blueberry yogurt for the proper purple/blue on one page—and no page was completed until I'd applied my patented 'sweat' droplets, something I'd refined from how Spain Rodriguez drew beads of sweat into a more painterly, very tactile rendition of sweat droplets.

|

| Page 63 of Bissette and Veitch's 1941:The Illustrated Story, where their use of organic material on the page can be observed. |

Anyhow, we somehow got it all done without Rick actually killing me (though I no doubt deserved death), and close enough to deadline for the book to see print, somehow. And that last day, before we took the bus to NYC to deliver the last of the book to John Workman, we laid the pages out on the slat wooden floor of the schoolhouse to take a long last look at the end of the whole thing. Rick passed me a joint he'd rolled, and we smoked that celebratory joint, and stared and stared at the pages, and figured we were all done now...

...and then the landlord's dog Banjo came bounding into the schoolhouse, soaking wet from bounding through the stream that ran in front of the schoolhouse, and Banjo shook the water off as soon as he was in proximity of our artwork. We went apeshit!

Poor Banjo had no idea why we weren't overjoyed to see him, why we were yelling and spazzing out and I hustled him out the fucking door and slammed it, and Rick and I couldn't fucking believe it. Of course the water drops were spattered all over our pages of original art, discoloring the dyes and watercolors and colored pencils and wrinkling the pasted-down collage components! Instead of basking in the glory of a job well-done and finally done and moseying off to the bus and to NYC, we spent the bulk of that day repairing and restoring the pages as best we could, having to fix what we'd already finished. We somehow got it done and to John Workman, but all I really remember is that moment with Banjo, happy as can be, shaking off standing right over the pages. Holy shit!!!

...and then the landlord's dog Banjo came bounding into the schoolhouse, soaking wet from bounding through the stream that ran in front of the schoolhouse, and Banjo shook the water off as soon as he was in proximity of our artwork. We went apeshit!

Poor Banjo had no idea why we weren't overjoyed to see him, why we were yelling and spazzing out and I hustled him out the fucking door and slammed it, and Rick and I couldn't fucking believe it. Of course the water drops were spattered all over our pages of original art, discoloring the dyes and watercolors and colored pencils and wrinkling the pasted-down collage components! Instead of basking in the glory of a job well-done and finally done and moseying off to the bus and to NYC, we spent the bulk of that day repairing and restoring the pages as best we could, having to fix what we'd already finished. We somehow got it done and to John Workman, but all I really remember is that moment with Banjo, happy as can be, shaking off standing right over the pages. Holy shit!!!

BD -And Spielberg ended up writing a letter to the editor complaining about the end result (all the while giving props to the artists. How did this make you feel?

SB- Well, that was funny. It was both a badge of honor and a last kiss-off, wasn't it?

Truth to tell, so many of our creative decisions had been fueled by our frustration with how uncooperative Spielberg and the studio people were. We did all that work in a vacuum; we didn't even have an editor, really, John Workman was the only meaningful contact we had with anyone at Heavy Metal, so John was both our editor and our audience. John loved what we'd done, and told us so repeatedly. But the movie people just kept tying our hands: that whole crazy thing with having to steal reference materials, the script. We were under contract to do the job with them, for them, and we were treated like the mutant relative you shut up into the basement or attic, so fuck 'em. That fed the maniacal ire we poured into the adaptation.

I remember looking forward to drawing Toshiro Mifune and Christopher Lee as the Japanese sub commander and meddling German officer, only to be told early on that we couldn't use Mifune's likeness—as it was explained to us at the time by John Workman, Mifune had it in his contract that his likeness could not be used in any way to promote the film. So, being denied the honorable route of delineating one of my personal cinema heroes who was actually in the movie, Rick and I decided, fuck it, we'd embrace the rampant xenophobia we found all over that year of Life magazines from 1941 and we'd go the route of parodying such racism by caricaturing the Japanese in the ways they were hideously caricatured in the animated cartoons, comic books, and anti-Axis propaganda of 1941 and WWII. We embraced it and made it essential to our Kurtzman/Elder approach to the whole adaptation.

|

| Fully embracing WWII xenophobia and racist portrayal of Japanese characters as an answer to legendary actor Toshiro Mifune's refusal to let his likeness be used in promotion for the film. |

No doubt that, more than anything, ticked off the Hollywood folks and Spielberg, but fuck 'em. Fuck 'em then, fuck 'em now. We shamelessly ran with it, and thankfully most folks got it: that we weren't being racist or sexist, that we were satirizing the implicit and explicit racism & sexism of that era, and, truth to tell, the 1941 movie itself.

So, ya. Spielberg's letter was a perverse sort of vindication, actually. I'm still proud of that artifact. It only adds to the afterglow, confirms our 'bad boy' cartoonist intentions and chops.

I'll tell you what was harsher for me, anyway: the reactions we got from our mentor and elders. I don't think Joe Kubert 'got' what we'd done, and it was of course our backlash against all the DC war comics we'd been doing artwork and back-up stories for. One of our beloved Kubert School teachers, Lee Elias, called it "a glorified paste up job." Ouch. That hurt. Spielberg hating it was a point of pride by compare.

BD- Would you ever make another movie adaptation?

SB- I love and am addicted to cinema, and I love movie adaptation comics, but I've got to tell you, no. 1941: The Illustrated Story was a hard lesson in a lot of ways, but harder still were the lessons learned trying to work on a licensed Godzilla comic for Dark Horse in the late 1980s, then later see through a licensed adaptation of Night of the Living Dead for FantaCo Enterprises in 1989-1990. Both were clusterfucks, fucking nightmares, and both ended badly.

So, ya. Spielberg's letter was a perverse sort of vindication, actually. I'm still proud of that artifact. It only adds to the afterglow, confirms our 'bad boy' cartoonist intentions and chops.

I'll tell you what was harsher for me, anyway: the reactions we got from our mentor and elders. I don't think Joe Kubert 'got' what we'd done, and it was of course our backlash against all the DC war comics we'd been doing artwork and back-up stories for. One of our beloved Kubert School teachers, Lee Elias, called it "a glorified paste up job." Ouch. That hurt. Spielberg hating it was a point of pride by compare.

BD- Would you ever make another movie adaptation?

SB- I love and am addicted to cinema, and I love movie adaptation comics, but I've got to tell you, no. 1941: The Illustrated Story was a hard lesson in a lot of ways, but harder still were the lessons learned trying to work on a licensed Godzilla comic for Dark Horse in the late 1980s, then later see through a licensed adaptation of Night of the Living Dead for FantaCo Enterprises in 1989-1990. Both were clusterfucks, fucking nightmares, and both ended badly.

|

| Stephen Bissette's experience on Dark Horse Comics' 1987 GODZILLA comic book was a "Clusterfuck". |

People in comics go kind of crazy when there's any interface with Hollywood or movies. They bend over backwards for the movie people, pay out extraordinary amounts of money for the licenses, see to all the contractual matters for the rights—then you're essentially on your own to actually do the work, with constant meddling from multiple committee indecisions/decisions and nobody paying attention to what's necessary to do the work. They just want it done, even if they didn't see to completing the contracts for your part of the job, or adhering to the contracts if you have them in place, or seeing to the pay, and everyone wants to be co-writing it "with" you or the writer, and so on and so forth. It's a clusterfuck, or it quickly turns into one.

I had a very happy working relationship with independent filmmakers Lance Weiler and Stefan Avalos when they contracted me to work with Heretic to do a little DVD insert comic for the Heretic disc release of their movie THE LAST BROADCAST; I put together a team of Center for Cartoon Studies students and two fellow faculty members (novelist Sarah Stewart Taylor and poet Peter Money) during summer break, and we did the whole thing in less than four weeks, print-ready, and divvied up the money equally between everyone in the group. That turned out great, very neat, tidy, fun, and over in less than a month.

Then Lance and my son Daniel and I jammed on making a little fake 'Jack Chick' tract-like Christian comic book prop for Lance's solo feature HEAD TRAUMA, and that was a great deal of fun: Lance kept us involved, actually changed some of what he shot and edited to more organically shape the movie around the comic tract Danny and I drew portions of, make it integrate in really creative ways. That paid nothing, but it was by far the most rewarding and pleasant interaction of comics-and-cinema I've ever been fortunate enough to experience.

Then, an indy film producer saw THE LAST BROADCAST mini-comic, and decided they wanted one, too, for a sf-comedy they'd finished and were going to release on DVD. As with THE LAST BROADCAST mini-comic, I pulled together a great creative team of alumni and students, it was a summer break gig, good money offered, and—it became an interminable fuckup. In some ways, it reminded me of aspects of the 1941 gig, but Rick and I pulled that one off. This one was just impossible. The movie was supposed to be a comedy, but it wasn't the least bit funny. In fact, it was agonizing to try to even pretend the people who made it understood "funny." They wanted the comic to be "funny,: though, but they didn't know what was funny, as their movie amply demonstrated: they didn't want an adaptation, and they didn't want us satirizing their work, either, so it was impossible, but we soldiered on. As we turned in work, the filmmakers kept running our work past "their committee," and kept requesting changes after changes, and it dragged on for weeks. By the time they were making changes to their own changes, I pulled the plug on the whole thing, and paid the students out of my own pocket what they would have earned had the filmmakers not stiffed us. They'd done the work, after all, and then redid the work, but the work wasn't the problem, the client was the problem.

To top it all off, after finding out I'd paid the students myself, the filmmakers chastised me: "you're teaching them the wrong lesson here," blahblahblah. Nope, never again.

Would I work with Lance Weiler again? You bet I would. But Lance is an artist, an incredibly adventurous and active artist, and that's not what "adapting a movie into a comic" involves.

Would I work with "movie people" again, on a comics adaptation? No fucking way.

I had a very happy working relationship with independent filmmakers Lance Weiler and Stefan Avalos when they contracted me to work with Heretic to do a little DVD insert comic for the Heretic disc release of their movie THE LAST BROADCAST; I put together a team of Center for Cartoon Studies students and two fellow faculty members (novelist Sarah Stewart Taylor and poet Peter Money) during summer break, and we did the whole thing in less than four weeks, print-ready, and divvied up the money equally between everyone in the group. That turned out great, very neat, tidy, fun, and over in less than a month.

Then Lance and my son Daniel and I jammed on making a little fake 'Jack Chick' tract-like Christian comic book prop for Lance's solo feature HEAD TRAUMA, and that was a great deal of fun: Lance kept us involved, actually changed some of what he shot and edited to more organically shape the movie around the comic tract Danny and I drew portions of, make it integrate in really creative ways. That paid nothing, but it was by far the most rewarding and pleasant interaction of comics-and-cinema I've ever been fortunate enough to experience.

Then, an indy film producer saw THE LAST BROADCAST mini-comic, and decided they wanted one, too, for a sf-comedy they'd finished and were going to release on DVD. As with THE LAST BROADCAST mini-comic, I pulled together a great creative team of alumni and students, it was a summer break gig, good money offered, and—it became an interminable fuckup. In some ways, it reminded me of aspects of the 1941 gig, but Rick and I pulled that one off. This one was just impossible. The movie was supposed to be a comedy, but it wasn't the least bit funny. In fact, it was agonizing to try to even pretend the people who made it understood "funny." They wanted the comic to be "funny,: though, but they didn't know what was funny, as their movie amply demonstrated: they didn't want an adaptation, and they didn't want us satirizing their work, either, so it was impossible, but we soldiered on. As we turned in work, the filmmakers kept running our work past "their committee," and kept requesting changes after changes, and it dragged on for weeks. By the time they were making changes to their own changes, I pulled the plug on the whole thing, and paid the students out of my own pocket what they would have earned had the filmmakers not stiffed us. They'd done the work, after all, and then redid the work, but the work wasn't the problem, the client was the problem.

To top it all off, after finding out I'd paid the students myself, the filmmakers chastised me: "you're teaching them the wrong lesson here," blahblahblah. Nope, never again.

Would I work with Lance Weiler again? You bet I would. But Lance is an artist, an incredibly adventurous and active artist, and that's not what "adapting a movie into a comic" involves.

Would I work with "movie people" again, on a comics adaptation? No fucking way.

Comments

Post a Comment