Movie Review: BLACK PANTHER - Black Powered.

Black Superheroes don’t have it easy. More often than not,

in the movies, they have been relegated to sub-par lemons (The abysmal CATWOMAN,

the embarrassing STEEL), uninspired parodies (The puerile BLANKMAN , the well-intentioned yet flawed METEOR MAN or the messy HANCOCK ), or they end up in mere supporting

roles in films like like X-MEN , CHRONICLE , SUICIDE SQUAD, and in the Marvel

Universe films.

Ever since the seventies, where the emancipation of African

Americans in the movies went from the ‘’proper indignation’’ of Sydney Poitier

to the rollicking badassery of Richard Roundtree or Pam Grier, they have not

benefited from much representation in the superhero genre until more recently

(Save maybe for ABAR, THE FIRST BLACK SUPERMAN (Frank Packard, 1977) who was using omnipotent

god-like powers to change the world around him. He might have had powers, but

to call him a superhero would be a bit of a stretch).

The late 1990s did bring forth BLADE (Stephen Norrington, 1998) and SPAWN (Mark A.Z. Dippé, 1997), a welcome

step in the right direction as far as treating black superheroes on screen with

a certain respect. Yet they were rather conflicted antiheroes instead of

full-blown virtuous superheroes. Still, it was refreshing to have super-beings representing

the black community in films that were not either embarrassingly bad, or

relegated to the background. This will most likely hit a new peak with this

month’s release of BLACK PANTHER (During Black History month, no less. The

significance of which has not been lost to many) which is set up to

do for black superheroes what WONDER WOMAN did for superheroines.

|

| The first and only issue of All-Negro comics which featured for the first time positive black characters as the heroes. |

Black superheroes have come a long way since LION MAN who

graced the pages of the only existing issue of ALL-NEGRO COMICS in 1947. That

this first attempt at more positive black archetypes in comics comes right

after World War II is no coincidence, as African Americans who were coming back

from a war where they fought alongside their white neighbours and experienced a

non segregated life overseas, which was so different from their reality in the US, brought forth a welcome sense that something had to be done to step

out of the stereotypical mess that permeated popular culture of the time. Arguably

not a superhero in the truest sense, LION MAN announced the Black Panther’s

scientific knowledge and toughness, and offered a black character in comic

books that wasn’t a caricature like Ebony in Will Eisner’s THE SPIRIT, Smokey

in JOE PALOOKA (a valet character that disappeared from the strip in the early

forties after complaints from the National Association for the Advancement of

Colored People, AKA the NAACP) or a manservant like Lothar in Lee Falk’s Mandrake.

|

| Even legendary comic book artist Will Eisner was able to feature grotesque racial caricatures in his otherwise groundbreaking work. |

Lothar is a typical yet interesting case; While he had superhuman

strength and was the ‘’Prince of Seven Nations’’, he rejected the chance to be

king to follow Mandrake in his adventures and be, as it was put in a 1935 story,

‘’a giant black slave’’. Hardly a fair trade off, and completely unrealistic. He did go through a bit of a change in 1965 when Fred

Fredericks took over the strip and started speaking ''proper'' English and

wearing more distinguished attire. In a way, he probably became a proper superhero

at that point, yet his past still weighed heavily and the role he was given still was barely more

than a glorified sidekick.

|

| Mandrake's colossal manservant Lothar, before he joined the modern world and left his days of servitude behind. |

|

| Lothar's evolution from ''black slave''. to heroic manservant, to colossal sidekick. |

This transformation of Lothar in 1965 is more than likely a

direct effect of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, signed by President Lyndon

Johnson, that declared illegal any kind of discrimination based on race, color,

gender, faith or origin. Emancipation was in the air, and stars like Harry

Belafonte, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Sammy Davis Jr., Dick Gregory and Sidney

Poitier were the living embodiment in the media of the fight for equality. It

was only a matter of time until comic books would get into the game. The Civil

Rights Act should have been the push that was needed for publishers to feel

more confident about having black heroes in comic books. 1965 even saw the

first black character to have his own comic book series. LOBO only lasted two

issues, however, which turned out to be due to distributors getting cold feet.

Artist Tony Tallarico remembers: ‘’ We did the first issue. And in comics, you

start the second issue as they're printing the first one, due to time

limitations. ... All of the sudden, they stopped the wagon. They stopped

production on the issue. They discovered that as they were sending out bundles

of comics out to the distributors [that] they were being returned unopened. And

I couldn't figure out why. So they sniffed around, scouted around and

discovered [that many sellers] were opposed to Lobo, who was the first black

Western hero. That was the end of the book. It sold nothing. They printed

200,000; that was the going print-rate. They sold, oh, 10-15 thousand.’’

|

| Dell Comics second and last issue of LOBO, which featured the first black hero to be featured in his own comic book. |

By the mid-sixties, one would have hoped that the presence

of black actors in popular movies (Sidney Poitier had been nominated for a

Golden Globe for A PATCH OF BLUE in 1965) on TV (the popular series I, SPY with

Bill Cosby was in its second season and Sammy Davis Jr had his own show.) and

music (Diana Ross and The Supremes were topping the charts), it shouldn’t have

been such a challenge to have a black character in comic books. Taking from black culture was more common than being inclusive.Yet it seemed

like the last bastion of popular culture where integration was difficult was the ''Funnies'', as

KERRY DRAKE’s creator Alfred Andriola would say in an EBONY article fromNovember 1966: ‘’Let’s face it. You can’t deal with race or color in comics. A

colored maid or a porter brings on a flood of letters. And if we show the negro

as the hero, we get angry letters from the South.’’ As another cartoonist would

say: ‘’If an editor gets one letter complaining about something, it carries

more weight than 100 good ones. If one cartoon amuses 100,00 persons but

offends one, the editors make you change it.’’ As one editor would explain,

there was just no ‘’advantage’’ to bring a black character in a strip. ‘’If I

were a cartoonist, I wouldn’t want to be a crusader, especially if I felt I

would lose the strip.’’

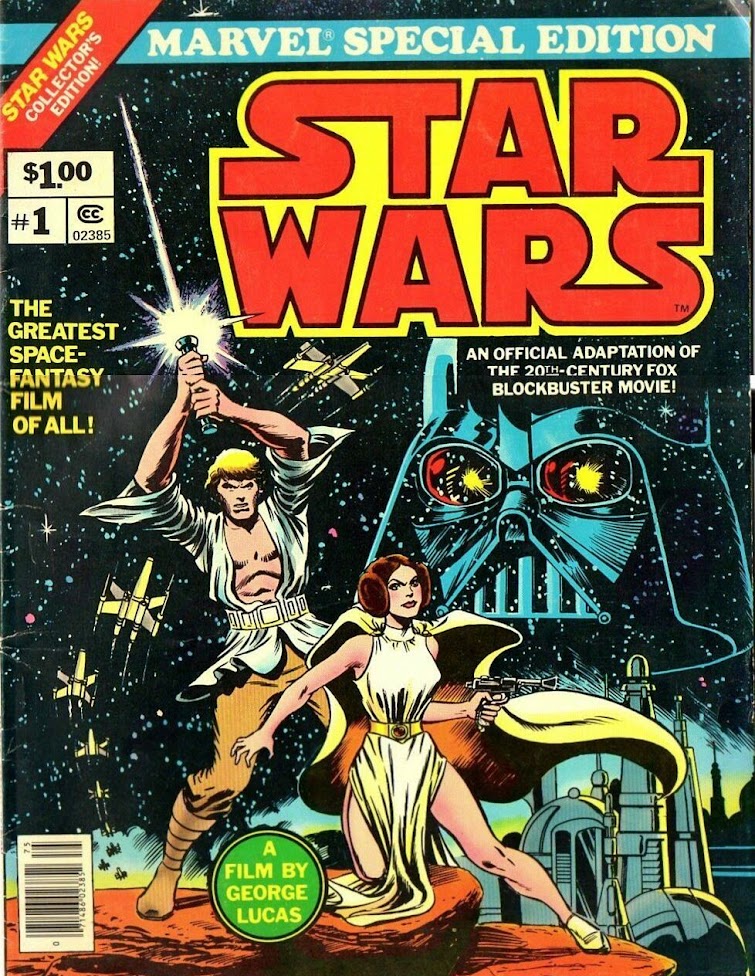

In the midst of this controversy, in July 1966, Stan Lee and

Jack Kirby introduced in Fantastic Four #52 the Black Panther. a mysterious

character who was agile and crafty enough to successfully confront the super-powered

quartet. (Until he loses ‘’The element of surprise’’, as Reed Richard glibly

puts it, as the Fantastic Four finally defeat their opponent).

What set the Black Panther apart was the fact that he was black. And while

like many other African comic book characters before him, whether it was Lothar, Waku, or Natongo from The Brothers of the Spear, he was the sovereign

of his nation. Yet his kingdom Wakanda was a highly advanced technological

society, something that went against all the usual clichéd stereotypes of the ‘’noble

savage’’.

|

| The Fantastic Four's arrival in the High-tech world of Wakanda, in FANTASTIC FOUR #52. |

The Black Panther was extremely smart and wealthy, and was nobody’s

manservant. Considering how tricky it seemed to be putting a black hero in a

comic book at that point, some may feel that Lee and Kirby were taking a big

risk. However, efforts had been made to lessen the ‘’shock’’ of potential

racist readers who might not have picked up an issue off the rack if it

portrayed a black character on the cover. We know now the Black Panther as

wearing the black suit and full mask obscuring the whole face. However early

versions of the character revealed more about his ethnicity.

If you forget the garish colors, the cut of the costume is

very similar to the finished product, with the notable exception of the

uncovered face. Stan Lee sent back Kirby to the drawing board, and changed the

name to Black Panther (which makes more sense since tigers are indigenous to

India, not Africa), and asking for a simpler color palette. It’s not impossible

that an article that ran in the August 5, 1966 edition of New York Times about the 1965 Black Panther Party

may have

influenced that name change, as it was published at roughly the same time Lee and Kirby were working on their story. More on the Party later. As for the black look of the costume, it's not impossible that Stan Lee went back to a bad guy he had co-written with Al Hartley in 1965 called the Panther, in TWO-GUN KID #77.

A first version of the cover was ready to go when someone apparently got cold feet.

A first version of the cover was ready to go when someone apparently got cold feet.

A new change was brought so that the Panther’s mask ended up

covering his whole face. This way, his appearance on the cover wouldn’t betray

his race, and wouldn’t affect sales. By the point he reveals his identity by

the end of the story, the comic had been purchased and Marvel had the reader’s money.

Black Panther’s first few years were rocky; he appeared as a

guest star in many other Marvel comics after his debut and even became a

member of the Avengers by 1968. But he wouldn’t get to headline his own comic

until 1973 in JUNGLE ACTION. In the meantime, he even managed to go through an

identity crisis and changed his name for a few months in 1971-1972.

|

| FANTASTIC FOUR # 119 (February 1972), when Black Panther became Black Leopard. |

It seems that the editors at Marvel were starting to get a

bit nervous about being associated with the political movement of the same name

who happened to burst onto the scene a few months after the character made his

first appearance in 1966. Contrary to some rumours, the Black Panther movement

actually got their name not from the comic book, but from a political party in

Alabama created in 1965 by Civil Rights Activist, and creator of the rallying

cry ‘’BLACK POWER’’, Stokely Carmichael. He would explain the choice of the

name in a speech:

"In Lowndes County, we developed

something called the Lowndes County Freedom Organization. It is a political

party. The Alabama law says that if you have a Party you must have an emblem.

We chose for the emblem a black panther, a beautiful black animal which

symbolizes the strength and dignity of black people, an animal that never

strikes back until he's back so far into the wall, he's got nothing to do but

spring out. Yeah. And when he springs he does not stop.’’

Certainly, this applies to T’Challa himself.

|

| The 1965 leaflet promoting the Black Panther Party. |

As the presence of black performers in the media increased

in the late sixties and through the seventies, and as Blaxploitation movies

became all the rage, more black superheroes would appear: The Falcon, Luke

Cage, Black Lightning, John Stewart’s Green Lantern…some of them having their

own titles. More often than not, the characters‘ race would be a springboard

for a strange mixture of social commentary (Dennis O’Neil and Neal Adams’

legendary run on GREEN LANTERN) and occasional outright caricatures (the embarassingly racist portrayal of Black Mariah in Luke Cage). The Black Panther may have opened a door, but

it was hardly a floodgate. The process of bringing black superheroes to comics was

slow and not without awkward controversies.

|

| The unfortunate portrayal of Black Mariah in Luke Cage #5 (January 1973) |

|

| John Stewart confronting a racist presidential candidate in GREEN LANTERN #87 (December 1971) |

But here we are now, over 50 years after his creation, and a

couple of years after his first spectacular live-action appearance in CAPTAIN AMERICA: CIVIL WAR, THE BLACK PANTHER is now a major motion picture.

Following the events in CIVIL WAR, T’Challa (the appropriately

regal Chadwick Boseman) is crowned king of Wakanda, a highly advanced African

country which is camouflaged to the rest of the world as a simple third world

country. A form of isolationism not unlike the one used by the Amazons who

dissimulate Themyscira from the World of man in WONDER WOMAN (Patty Jenkins, 2017).

His leadership is soon challenged by Erik Killmonger (the

extraordinary Michael B. Jordan) who shatters at the same time T’Challa’s whole

belief system and set of values.

Like most Marvel films, it is fast paced and highly

entertaining, propelled by a rousing instrumental score by Ludwig Göransson

which combines orchestral flourishes with traditional African rhythms. The

sprinkling of more modern songs by Kendrick Lamar ends up creating a mood that

is a perfect reflection of Wakanda itself, a juxtaposition of futurism and

tradition.

|

| Wakanda's mix of ultra-modern and traditional, a perfect example of Afrofuturism. |

Also like most Marvel films, BLACK PANTHER suffers from a

formula that has plagued the series from the start. The villain of the piece is

often an ‘’evil’’ version of the hero. IRON MAN fights the IRON MONGER, HULK

confronts THE ABOMINATION, CAPTAIN AMERICA’s adversaries are also

super-soldiers (THE RED SKULL and THE WINTER SOLDIER), ANT-MAN faces the

YELLOWJACKET, DR. STRANGE is threatened by another magician, and here, the denouement of BLACK PANTHER implicates the same exact dynamic. It

doesn’t take away from the enjoyment of the film, but the recipe is starting to

feel a bit old.

Yet the energetic and emotional directing by the talented

Ryan Coogler, who had previously directed Michael B. Jordan in the grippingly powerful FRUITVALE STATION and the surprisingly powerful CREED, manages to make you

forget the special effects orgy by eliciting immensely compelling performances

by his actors, and injecting a sizable dose of social relevance within the otherwise

typical superhero action narrative.

Chadwick Boseman continues to portray the Black Panther with

an amount of dignity and strength that fits the character perfectly. But it is

his entourage of strong female characters that almost steals the show from him.

Letitia Wright as T’Challa’s sister Shuri is the genius of the family, a wise-cracking, no-nonsense woman who provides our hero both with new

technological marvels and a healthy dose of arrogance that reminds him that she

will not be impressed by his place on the throne.

Oscar winner Lupita Nyong’o plays

Nakia, T’Challa’s former lover (and still potential love interest) and Wakandan

spy. Nyong’o has more than proven her worth as a MVP in most films she has been

part of, and this one is no exception. Her openness to the rest of the World

provides an excellent counterpoint to the more conservative and isolationist

Okoye, played with gusto by THE WALKING DEAD’s very own Michonne, Danai Gurira,

who provides some of the film’s coolest action scenes (A particular car chase

includes a moment that had me wanting to stand up and cheer). This trio of

strong women not only offers great support for the main hero and amazing role

models for young girls (and young boys), but they are reason enough

for me to want to see a BLACK PANTHER 2.

|

| The kick-ass female cast of BLACK PANTHER. Letitia Wright, Lupita Nyong'o, Danai Gurira, and Angela Bassett as T'Challa's mother Ramonda. |

The aforementioned Micheal B. Jordan is a stand out as Killmonger

with a performance that is nuanced and at times poignant, which made this

reviewer tear up more than once. While his approach leaves something to be desired, one

cannot dispute his motivations and the source of his rightful anger at the situation

of black people around the World. He is pretty much the Malcom X to Black

Panther’s Martin Luther King (Something that was already echoed by Ian

McKellen’s Magneto and Patrick Stewart’s Professor X in Bryan Singer’s X-MEN.)

The theme is more of a subtle subtext in the film, as I can imagine Marvel and

Disney, like the comics publishers of yore, not wanting to ruffle too many feathers, but it is refreshing to see

such a huge blockbuster attempt to address the issues. In that way, Netflix’s

superb LUKE CAGE series and even the recent BLACK LIGHTNING TV series are more

daring in their approach regarding the themes of police brutality and the struggle against racial inequality.

|

| Michael B. Jordan as Eric Killmonger, one of Marvel Cinematic Universe's most endearing villain. |

The film does offer an occasional jab at the present

administration, especially when T’Challa, in an exemplary speech to the United

Nations, condemns the ‘’Folly of building barriers’’. Boom! We can bet that the powerful sense of

feminism expressed in the film would also displease the groper-in-chief.

It’s impossible not to talk about the apparent significance

and importance of the release of the film for the black community. With the

teaser trailer getting over 89 million views in 24 hours, and Fandango getting

record-setting ticket pre-sales, one cannot deny the excitement and anticipation this film has created. The NEW YORK TIMES magazine explains it very well in a recent article. It

seems a bit like the WONDER WOMAN effect, where a film featuring a powerful

female superhero, raised in a matriarchy, directed by a woman, ended up providing

a full sense of identification and validation for women everywhere. This time,

it seems that a film featuring a powerful black superhero, steeped in his own

racial identity and African culture, who is also part of a monarchy, was directed by an

African American and featuring a mainly black cast, may do the same for black

people. And isn’t Wakanda, like Themyscira is for women, a ‘’safe place’’ where

black people are dominant, untouched by white men. In the words of A WRINKLE IN TIME director Ava DuVernay,

“Wakanda itself is a dream state, a place that’s been in the hearts and

minds and spirits of black people since we were brought here in chains.”

In times when black people are denied votes by

gerrymandering and dubious voter ID laws and that a black person driving a car

fears for his life the moment he is pulled over by the police, there has long been the desire for a bulletproof hero like Luke Cage, the angry retribution of

Black Lightning, or the wisdom and dignity of Black Panther.

The time is ripe for the Black Panther.

Fantastic piece!! As both an African-American and a life-long comics nut my jaw has dropped to JUST find out about the ill-fated Lobo!

ReplyDeleteGreat history here.

Thanks. It's but a teaser of a much more complex and fascinating history.

Delete