THE MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN THE BIGFOOT. Movie review and Interview with director Robert Krzykowski and Star Sam Elliott

July

20th

2018.

Days

after having been denied an interview with legendary actor Sam

Elliott at the Montreal Fantasia Film festival (Too many journalists

had requested some of the limited time that was allocated for

interviews, and I was just too late to fit in), I get a call around

12.45, during my lunch break at work. A spot had freed up in an hour

to be able to sit with Sam Elliott. I was to have roughly 15 minutes.

I’m horribly unprepared, but still jumps at the chance. An hour

later, I am sitting in the press room, waiting for my chance to be

face to face with the velvet-voiced, epically mustached cowboy. Time

stretches and the distributor has other plans for his star, and I’m

starting to feel that I may not be able to do the interview.

Fortunately, I am soon lead to the green room, and am informed that

Robert Krzykowski, the director of the intriguingly titled THE

MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN THE BIGFOOT which stars the

grizzled sex-symbol, is also waiting in the room. Brief moment of

internal panic; as ill-prepared as I am, I am even less prepared to

discuss a film I haven’t yet seen with the director. I will have to

improvise, and am warned I have now 5 minutes to do the interview.

I step into the room, and am greeted by

the young filmmaker and the veteran actor. The 73-year-old thespian

gets up and firmly shakes my hand all the while staring deeply into

my eyes, his furrowed ebony brow hanging over his intense gaze. At

this moment, I understand right away why the guy is a star; the

charisma is oozing all over the room.

|

| Sam Elliott and Robert Krzykowski on the red carpet for the World Premiere of THE MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN THE BIGFOOT at the Fantasia Film Festival. (Photo by Julie Delisle) |

I get out my phone and a camera as back-up to record the interview, and proceeds to kneel down in front of the duo.

SAM ELLIOTT: That’s not going to be very comfortable. You should be comfortable. Sit. Please.

BD:

Thanks. (laughter) To

director Robert Krzykowski)

How did you think of Sam Elliott for that role?

ROBERT KRZYKOWSKI: We were

looking for an actor that had a very human quality and decency, and

also mythic and iconic, and the list was very, very narrow.

(Laughter). It was Sam, I mean, John Sayles spoke very strongly about

Sam. As well as our casting director Kellie Roy. We sent him a script

and I wrote Sam a letter explaining what this was and why the title

was so strange. He called shortly thereafter and it was a really nice

phone call. I didn’t know for sure if he’d do it or not but I

just felt very supported in that phone call, that he believed in it

and we knew it would be special if Sam was able to be part of it.

BD: (To Sam Elliot): How

do you feel when you get a movie with such a title?

SAM ELLIOTT:

It’s kind of like the audience is going to feel; They’re not sure

what they’re in for going in to see this film. When I first saw the

title I just thought: ‘‘This is going to be a fantastic

read…either that or it’s not going to be a good read at all.’’

(Laughter) And it was a fantastic read. The tale that’s told is so

much deeper and so much richer than the fantastic quality of the

title. When I read the script there was no doubt in my mind that I

wanted to be part of the film. I spoke to Robert over the phone and

as he said, he wrote me this letter that came with the script, and

the combination of all three just made me know this was something I

wanted to do.

BD: (To

Robert): And I know you

are very confident that the title itself is strong enough to sell

the film, and the poster too, which is amazing, because you didn’t

really cut a trailer for this.

ROBERT KRZYKOWSKI: No, we have a

trailer and we love it, but we wanted the first audience to…it’s

very, very rare…my favorite way to see a movie is to just know

nothing. And we felt that, either out of respect or whatever it might

be, we thought it might be special for that first audience to just

know nothing, and Epic was really supportive, there were a lot of

conversations about what do we put out into the world. We decided;

let’s keep it very minimal and let this audience experience it for

what it is. So in some ways, we built this whole movie for this

audience tonight, because after that, the word will be out on what it

is and what it’s like, why it is what it is, and it will be

received however it’s received, but I think that was a gift we

wanted to give to this audience because it’s rare.

BD: Well trust me, you have

probably the best audience you could ever wish for here. They are

terrific and you’re going to have a ball tonight. Enjoy your show

tonight.

That very evening, I sit with 700 other

patrons, filling the Hall Theater of the Concordia University to

capacity, ready to experience THE MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN

THE BIGFOOT.

The film starts with a broad yet

brilliant visual gag, as a young Nazi officer stares nervously at his

watch, preparing to meet with Adolf Hitler. The hands on the watch

are replaced by a swastika. A moment that would have been quite at home in a Mel Brooks comedy. But once we get back to present day,

where the young upstart played by Aidan Turner (Doing a pretty good

job of evoking Elliott) is replaced by a disenchanted Sam Elliott,

there is a distinct tonal shift in the film. Maybe this won’t be a

broad comedy after all.

Elliott plays Calvin Barr, who has

killed Hitler in a top-secret mission during World War II, and now

lives unassumingly in a small quiet town, trying to come to terms

with his past. His peace will be interrupted by envoys from the

government, cashing in on his legendary status to send him on a

mission to hunt down a germ-ridden Bigfoot somewhere in the Canadian

wilderness, and prevent a global epidemic.

Writer-director Robert D. Krzykowski

does an impressive high-wire act of shifting from the sublime to the ridiculous,

occasionally slightly losing balance in what is more attributable to the complex nature of the narrative than an actual lack of talent, and gleefully plays

with the audience’s expectations who was probably sitting in for a

wild, campy fantasist romp, but is instead offered a melancholic

exploration on the nature of heroism.

“It’s nothing like the comic book

you want it to be” says Elliott during a speech that deconstructs

the scope of his WW II accomplishment. It might as well be director

Krzykowski talking to his audience, as he offers moments of deep

introspection amidst the pulp trappings promised by the title.

Sam Elliott plays the lead with

reverence and strength, tapping in on the self-reflective streak he

has been on recently (THE HERO), and giving an award worthy

performance, making the most of his intensity and a great deal of

pathos. In a cinematographic landscape populated by aging heroes, he

is more Eastwood’s Bill Munny than Stallone’s Barney Ross. His

toughness is dampened by a potent sense of regret and even guilt, and

violence is a last resort that only leads to loss.

Production values are impressive for a

low-budget film, and the majestic musical score by Joe Kreamer

(MISSION IMPOSSIBLE: ROGUE NATION) helps to confer to the film

a sense of melancholic heroism. Special effects are by a dream team

of legends in the field, including Douglas Trumbull (CLOSE ENCOUNTERS OF THE THIRD KIND, BLADE RUNNER), Richard

Yuricich ( 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, STAR TREK: THE MOTION PICTURE),

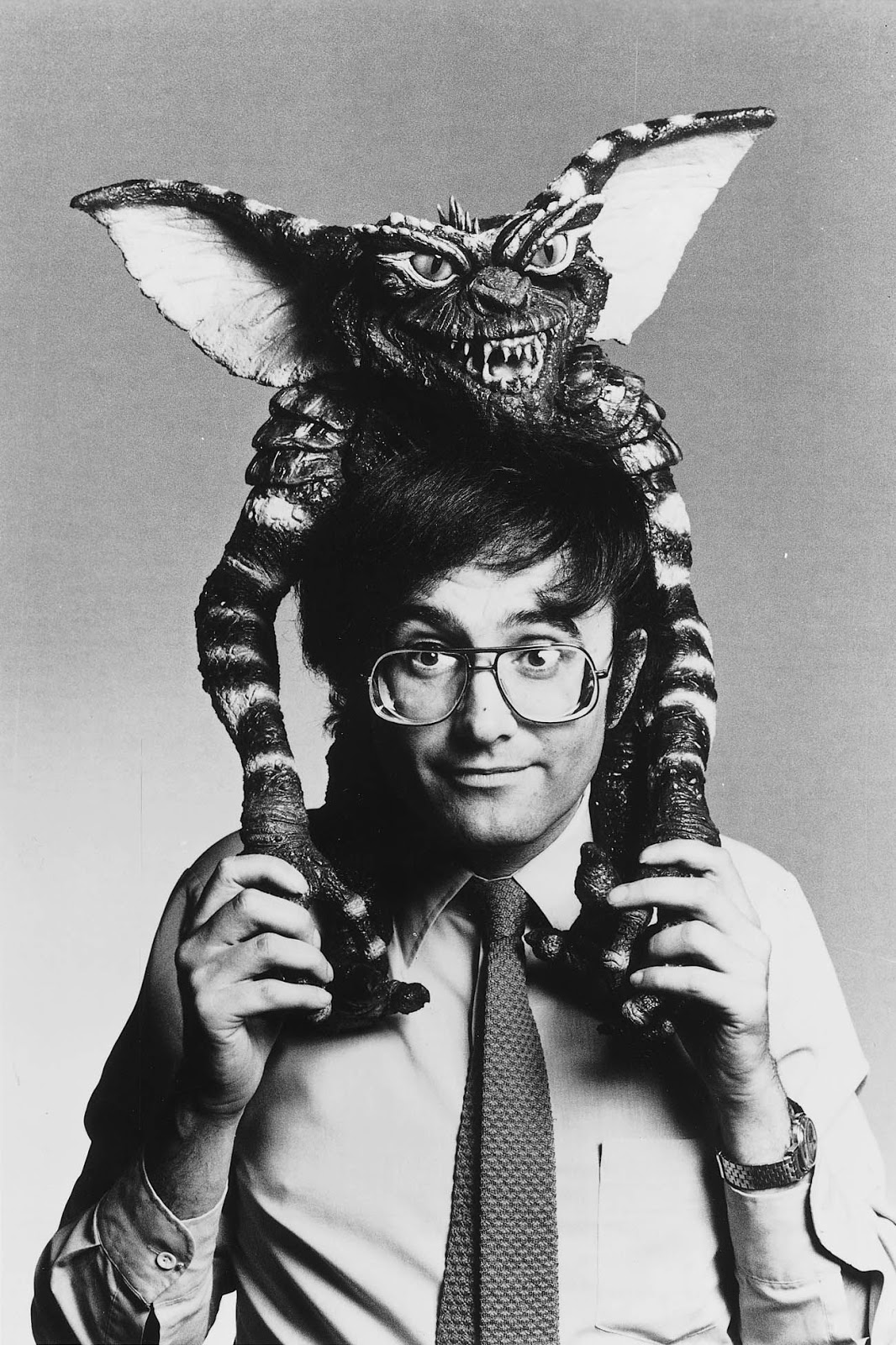

and Rocco Gioffre (ROBOCOP, GREMLINS) although it should be

noted this is not per se an effects heavy film.The effects featured are the best kind; the ones that you won't notice.

In the end, while the pulpish promise

of its outlandish title will attract fans of psychotronic cinema, and

insures that it will obtain an instant cult status, Robert D.

Krzykowski created so much more, and delivered a surprisingly deep film that will stand the

test of time.

After viewing the film, I had to

get in touch with the director who graciously accepted to answer more queries..

|

(Note: to avoid getting carpal

tunnel syndrome, THE MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN THE

BIGFOOT will be from now on referred as H&B)

BRAIN DEAD: You originally started up as a cartoonist, with an ongoing online series called ELSIE HOOPER which started way back in 2002. How old were you when you started it...?

BOB K. I was eighteen when I

started ELSIE HOOPER. A lot of the friends and collaborators

I’ve met in filmmaking came from the seeds of that little comic. A

solid readership kept it going through years of its kind of

steam-of-consciousness, experimental run.

|

| Chapter 425 of the ongoing web comic by Robert Krzykowski, ELSIE HOOPER. |

BD: What prompted you into

creating this series?

BOB K: I started ELSIE HOOPER

while studying journalism at UMass. Someone was sitting behind me in

class, saw me drawing a strip, and said I should put it in the paper.

I met poet and illustrator Dave Troupes through the UMass Daily

Collegian. He was doing his brilliant comic BUTTERCUP FESTIVAL

at the time. It was a whimsical, sometimes heady comic about a

representation of death that decides to embrace nature and philosophy

instead of doing his job. Dave’s strip was this lovely, beautiful

work that vacillated between broad humor and a really searching

exploration of something deeper—sometimes without words; like an

existential ‘Calvin and Hobbes’. Dave’s comic told me that the

Collegian was willing to take chances and be experimental.

|

| Dave Troupes' BUTTERCUP FESTIVAL, which inspired Robert Krzykowski to create his own web comic. |

So I got up the courage, walked down to

the basement of the Campus Center where the Collegian was staffed,

and I shared the first twenty or so comics of ELSIE HOOPER with

the editor there. He liked it a lot, and made it a serialized thing

that ran for several years. Since it was serialized, students would

contact the paper if they missed a day, so I realized there needed to

be a website so students could follow along independently. It became

one of the really early web comics that grew into this cult,

underground thing. I’ve met a lot of great people through those

black and white panels.

BD: Would you say being a

cartoonist is a good preparation for being a director?

BOB K: I always thought of the

comic strips as something akin to storyboards. So when it came time

to try to make H&B, I’d established this background in

visual storytelling. I drew hundreds of storyboards for H&B

while it crept through development. Those storyboards were carefully

utilized through every phase of production. Everyone had them for

prep, and on the call sheets during the shoot. Even if we didn’t

follow them exactly, it was a great starting point for conceptual

discussions. So yes—the comic was instrumental to my work as a

director. There was a clear notion of how the movie would look, how

the imagery would be framed, and how it would all generally come

together in the edit. There are whole sections of the movie that

appear as storyboarded, so it was pretty amazing to see those

drawings brought to life by a stellar team of artists like we had

here.

|

| Some of Krzykowski's storyboards for his short film ELSIE COOPER, based on his web comic. Copyright 2018 - Robert D. Krzykowski |

BD: You also made a short in

2016 based on the comic, using puppet animation. Is this a genre you

would want to explore further?

BOB K: ELSIE HOOPER is a

really fun journey through science fiction, fantasy, and noir. It’s

sweet and sometimes silly, and there’s all these meaningful asides

that comment on grief, loss, and depression—and what it feels like

to feel different from other people. I think the resolution will be

surprising and unique. It has a lot of action and black ink

splattered everywhere. It’s goes to some really unusual places to

reveal its intentions. That the audience always let me explore that

story freely—that was really rewarding.

If I ever make that as a movie, I just

need to feel it in my gut, and after all these years, I’d like to

distill the storytelling a bit. There’s an interest out there, and

I know it would make a lot of people happy to see it come to life

after all these years. The short is a really fantastic showcase of

what that could be. Looking at the world today, there’s a couple

other stories nagging at me first. Someday, if I’m lucky enough to

make ELSIE HOOPER with a team of effects wizards, animators,

and puppeteers—it would be a joy.

BD: It was an interesting choice

to make the short with puppets, so they look even closer to the

original illustrations. How is it to film using puppets?

|

|

| Lead puppeteer Sean Bridgers carefully conceals himself behind the Ridley Hooper puppet to create the illusion of a standing pose. Copyright 2018 - Robert D. Krzykowski |

|

| Actor and lead puppeteer Sean Bridgers who also voices Ridley Hooper. Copyright 2018 - Robert D. Krzykowski |

|

| Puppetmaker Vanessa McKee makes an adjustment to Ridley Hooper between takes. Copyright 2018 - Robert D. Krzykowski |

BOB K: Working with puppets is a

really wonderful thing. If the puppetry is good, you feel like

they’re alive—like you’re spending time with these characters.

Actor Sean Bridgers brilliantly voiced and puppeteered the lead

character, Ridley Hooper, and brought him fully to life. You look at

the monitor, and all you see is what you’re supposed to see, and

something inanimate suddenly has movement and life. All this is

taking place in three-dimensions, in real time, with physical light

scattered over real objects and their surroundings. So it’s this

wonderful surreality. And there’s this hidden ballet of trickery

that I love. You look beyond the monitor, to the set, and there’s

this contorted, sweaty team of focused people in black leotards

trying to hide themselves, and coordinate their movements, and

deliver a seamless, living performance. And every few takes, there it

is, and the make-believe is real. Creatively, it’s a wonderful

headspace. So, of course—I’d love to go back someday.

BD: One thing I noticed in ELSIE

HOOPER, which is reflected in H&B, is a refusal to

glamorize guns, and showing a certain sense of regret in their use.

Do you have a Love-Hate relationship with guns?

|

| A man and his gun. Conceptual drawing by Bob Krzykowski with final comparison image from the short. Copyright 2018 - Robert D. Krzykowski |

BOB K: I don’t think the

loudest voices are allowing for an open conversation that might lead

to something better. Gun violence disturbs me to my core. I think

this generation has shed a lot of tears watching the news unfold

around one tragic shooting after another. It’s shattering that we

hurt one another in this way. If someone safely owns a gun and they

don’t fetishize the power that comes with that ownership—fine. I

can respect that. But there are a lot of people that have an

unhealthy relationship with their guns. And that’s deeply worrying.

I believe we live in a violent culture,

and we can be cavalier about some of these very American storytelling

elements—like guns, violence, and the masculine hero that asserts

his power through carnage. In the real world, these things are

tragic. And they have repercussions. I’m trying to explore

characters that are effected by their choices. I want them to exist

in something resembling reality, even in a story such as this one

with elements that are fantastic or preposterous. I’m using a lot

of these elements as you would in a parable; to draw an illustration.

I’m trying to write from an honest place. There’s a basic truth

about our relationship with killing, and we have to reconcile that

before we can ever move forward as a people. No life is worth the

exchange rate we’re paying right now.

BD: Movies have long associated

guns with heroism, but Sam Elliott’s character seems to resent

having to use them to fit that limited definition of heroism.

However, there is a sense of unrelenting decency about Calvin Barr

(The scene when he returns a lottery ticket to a convenience store is

a good example). What is your definition of a hero?

BOB K: You used the word I would

have chosen. Decency. My grandfather was a hero to me because he was

decent. He was a soldier in WWII, he worked for years at GE, and he

raised a big, beautiful family. I don’t think I really knew the

word when I was little, but I understood it later on by my

observations of him. So many good things blossomed from his decency.

If someone lives by that code, and they allow that goodness to grow

and expand as they age and mature—to me, that’s a hero. It’s

not about physical strength or material wealth. Those things come and

go. It takes mental toughness to overcome our lesser selves, and to

strive to be decent. There’s a few billion people out there trying

to do the exact same thing, and I’m sure you know a few. I sure do.

Something to aspire to.

BD: The theme of the aging hero

has been a staple of pop culture in recent years, but it feels like

you fall more in the UNFORGIVEN category than Miller’s DARK KNIGHT RETURNS or THE EXPENDABLES.

BOB K: My parents encouraged I

make friends with older people every chance I got. In high school, I

worked evenings in a nursing home in Western Massachusetts. I saw the

loneliness and isolation there. I’ve never been able to shake the

faces of those people at their happiest—and at their lowest. My

biggest fears are loss and regret. And those are the primary themes

of this movie. I’m sure that’s no coincidence.

UNFORGIVEN is the ultimate

deconstruction of the American western because it lays people bare to

their most flawed, petty, imperfect selves. Everyone seems cursed and

fated. I think Gene Hackman’s work in that film might be among the

finest performances of all time. He’s my favorite actor—both he

and Walter Matthau. They always felt like completely real, flawed

human beings. That really interests me.

BD: I have to agree.

BOB K: UNFORGIVEN is one of the great

American films because it’s totally honest about how ugly and

imperfect we can be. There’s no heroes. It doesn’t glamorize its

violence. It’s human. In the end, it leaves you feeling strange and

conflicted. I love how symbolic UNFORGIVEN is. Hackman’s

idyllic homestead is turning out to be this poorly measured, uneven

house. His best intentions wind up manifesting themselves as this

cockeyed, crooked thing—not unlike himself. That’s most of us, I

think.

BD: It’s a totally different

approach to aging heroes than THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS or THE

EXPENDABLES.

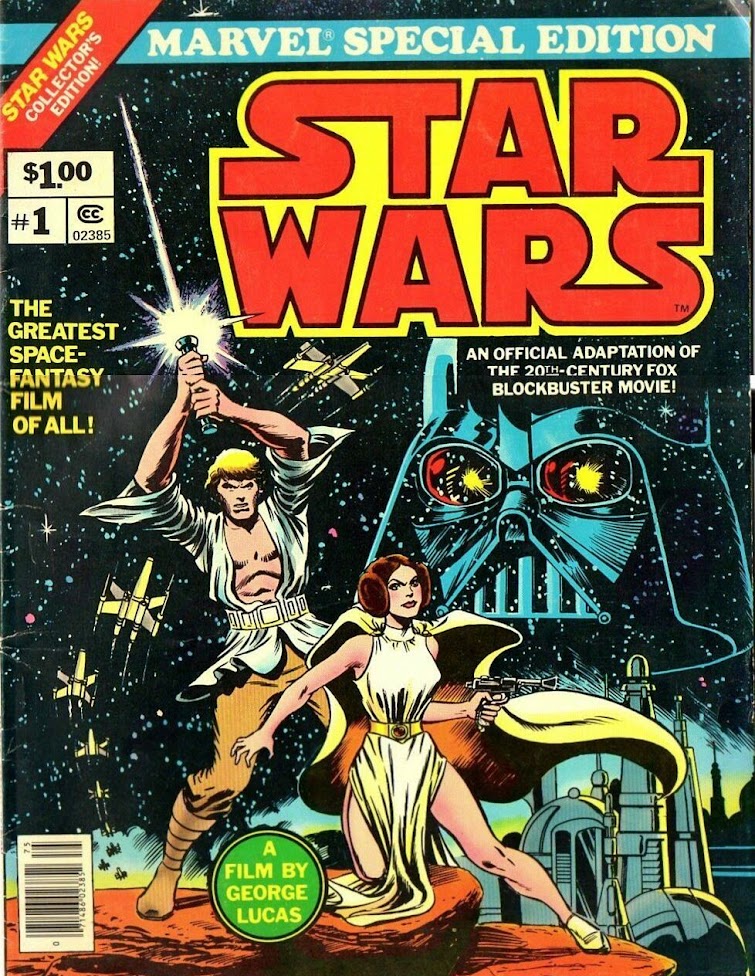

|

| Another side of the aging hero. Original artwork by Frank Miller for the Cover of issue 2 of THE DARK KNIGHT RETURNS (1986) |

BOB K: I admire THE DARK

KNIGHT RETURNS, but it’s totally fascist and cruel. It

deconstructs the mythic heroes in its pages to lay them bare and

subvert them in a fit of punk revolt. It’s an angry work, and it’s

the perfect Batman story for its time and place—and maybe more

timely now than ever. Frank Miller’s exploration of violence, duty,

and masculinity remains pretty bleak, but essential. H&B

pivots to something more hopeful, and I think there’s a place for

that too—studying different kinds of mythic heroes and heroism

through different lenses.

As for THE EXPENDABLES, I see

those movies as big budget cartoons meant to make people laugh and

high five each other. They’re not mean-spirited, and they don’t

resemble reality. It’s a bunch of action legends coming together to

have fun and deliver for their fans. I’m neither here nor there on

it.

BD: Stallone is worth more than

this as a filmmaker.

BOB K: I’m much more

fascinated with the Stallone that wrote ROCKY—one of the

most tender, heroic American movies ever. It reminded us that a hero

can lose and still win in every way that matters. I’m taken by the

Stallone that acted in COP LAND—one of his most sensitive,

understated performances. Stallone is seriously gifted. I wish he did

character work more often. He’s a really moving, intelligent actor.

I wonder if he has any scripts squirreled away that don’t match his

superstar persona, but that he’s always kinda wanted to get to. I’d

love to see him venture off into a role that pushes him into

uncharted waters. He goes there now and again, and I’m always

enthralled. He’s really great in the last two ‘Rocky’ movies.

Again, he’s a gifted writer. His story sensibilities are all over

those movies. How did you get me talking about Stallone? (laughter).

BD: When I first read about H&B,

I have to admit that at first, I was expecting something like

Coscarelli’s BUBBA HO-TEP, but while both films deal

beautifully with a great sense of melancholia, yours is way more down

to Earth.

BOB K: The very first person to

congratulate Lucky (McKee) and I when H&B was first

announced was none other than the great Don Coscarelli. Literally the

first words of encouragement from any friend or colleague came from

Mr. Coscarelli in a lovely email to Lucky first thing that morning.

It felt cosmic and special that he would be the first person to reach

out and wish us luck on this journey. I don’t know him at all, but

that was special to both of us. He’s a supremely talented filmmaker

that also seeks to illuminate some truth amidst the fantastic and

surreal, so if you found some symmetry here, that puts us in great

company.

BD: Bruce Campbell gave in

Coscarelli’s film a lovely portrayal of a forgotten hero on the

decline.

BOB K: Bruce Campbell was my

first print interview ever at the UMass Daily Collegian. I still have

that interview on an old tape recorder. He’s a hero of mine, going

way back to BRISCO COUNTY JR. which I followed obsessively as

a little kid. Bruce was kind and supportive when I got pulled into

film while I was still in college. Some producers in LA had found my

comic online, and wanted to make a movie of it. Bruce gave some

pivotal advice so I didn’t fall into any traps in those early days.

Just a lovely person, and great to his fans—generous. I’ve never

met him in person. Lucky worked with Bruce on THE WOODS. They

had a great collaboration there. Really striking, visual, textured

movie.

BD: Back to H&B. in

the film, Sam Elliott’s character says: “It’s nothing like

the comic book you want it to be”. Was it important for you to

go beyond the audience’s expectations?

BOB K:

There was never a conscious attempt to radically subvert expectations

with this film. This wasn’t written in rebellion. I wasn’t

writing to counter anyone or anything. It was a gentler intention

than that. I was very aware of the expectations of that title. That’s

true. But it was made with a lot of respect to a thinking audience. I

trusted their ability to track the story organically and let it ebb

and flow as it would. That’s the joy of discovery. I felt like we

were inviting audiences into something surprising—inviting them to

discover something worthwhile. That was the spirit in which this was

made. I didn’t want to put the audience in a passive role. At its

core, this is a simple character study. But it leaves enough room for

interpretation that the audience can participate in the storytelling

and feel welcome to own a piece of it as they exit.

BD:

So in a way, you wanted to go beyond the myth.

BOB K: Whenever the storytelling

crept close to pure mythologizing, I would pivot to something that

felt a bit more human or grounded. All the characters, great and

small, seemed to have something to say about how we treat one

another, and I wanted to follow those impulses through to their

logical ends. So that was the balance I needed to find. And it’s

not an easy line to ask an unsuspecting audience to walk with you.

That central speech you mentioned is

very much intended as a moment to speak to a certain sector of the

audience, and to let them know that they’re still in good hands. I

wanted to say that we’re aware of what we’re doing here, and it’s

okay to leave your expectations behind now. There’s more to be

discovered here if you’ll just trust us, and let the story and the

film-making take you there. And in that, I think there’s the joy of

discovery, and taking something away with you.

BD: Am I wrong in thinking that

constant pebble in Calvin’s shoe is his regret of being unable to

profess fully his Love to Maxine? If so, in that particular way, he

reminds me a lot of Anthony Hopkins’ character in REMAINS OF THE DAY.

|

| Caitlin FitzGerald as Maxine, the object of Calvin's affection in THE MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN THE BIGFOOT. |

BOB K: I haven’t seen that film, though I will seek it out upon your recommendation. The pebble in the shoe is emblematic of so many things Barr has been carrying with him. Biggest of all is the void that Maxine left in him. With the pebble, something small is released. There’s a change, however small. Sam plays that moment splendidly. That shot of him smiling down. It’s hopeful. We so want Barr to find his peace. At the eleventh hour, Barr finds a couple symbolic moments of hope and connection in that graveyard, and it’s really moving to see how Sam conveys all this so simply through his weary body language and a warm, rare smile that signifies we can finally exhale with him.

BD: He certainly does. Sam has a

heck of a warm smile (makes my wife melt every time she witnesses

it). A thing I noticed that was common to both ELSIE HOOPER

and B&D, both films

start with the main character looking at a watch. The passage

of time seems to be an important theme in B&D.

BOB K: Time and watches play a

big part in ELSIE HOOPER.

There, time seems to be standing still. Or is it a trick of the mind?

Or something else? Yet to be seen.

In H&B, time is incredibly

nebulous and untethered. There, each timeline is dependent on the

narrative weight of the other. The story can’t work without one

timeline interacting with the other. This isn’t a time travel

movie, but it reveals information in a very similar way to the

classic time travel films. Information is withheld and revealed to

color and expand the story as it develops. Looking forward, we look

back. And back, foreword. Each timeline becomes more meaningful

because of the gravity of the other.

BD: This

non-linear approach to storytelling must present its own set of

challenges.

BOB K: Editor Zach Passero and I

saw the edit between timelines as a series of waves gently coming in

and going out. We wanted the flashbacks to feel equally immediate to

the 1987 timeline—never obtrusive. There were carefully designed

transitions in the script and storyboards. They were meant to help

create cohesion and flow.

There were a hundred ways to weave the

edit of a film like this. We chose the path that highlighted the

emotional peaks and valleys without giving the audience whiplash.

That said, there are a couple moments that are specifically

structured to goose the audience and direct their attention in a much

more radical way. The two timelines are having a conversation with

one another—and hopefully the audience feels a participant in that

conversation as opposed to a passive observer. It certainly asks a

certain amount of patience and interaction, and I hope that patience

is rewarded in the end.

|

| Sam Elliott tracking the Bigfoot in THE MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN THE BIGFOOT. |

BD: Is Calvin Barr’s killing of the Bigfoot a way to also destroy the legend that he has become by eliminating Hitler all those years ago?

BOB K: Barr doesn’t feel he

contributed anything to history, so I’m not sure he buys into his

legend at all. But we in the audience do, because we see it from the

outside. He was never able to square himself with the notion of

killing someone. Even if that someone was Adolph Hitler. If you’re

gonna have a mythic story question the very nature of killing—who

better at the center of that question than the one person everyone

says they’d happily travel back in time to kill? There’s a

‘Twilight Zone’ element to this. And it’s a conundrum.

Barr is a good man. He doesn’t

believe in killing, yet he’s a natural at it. Barr killed Adolph

Hitler, recognized him as a monster, but the act took something of

his soul. And it didn’t alter the war in any meaningful way.

History marched on just like you read about. So he exchanged his life

and his happiness in the service of others.

The fact that Barr comes home in the

end might have surprised him more than anyone else. If he believed

anything about his legend, it might be that he’s cursed—or

doomed. Once Barr comes home, I think he’s changed in some subtle

way. He’s able to abandon the legend set forth in the film’s

title. In the end, Barr simply becomes “the man”.

BD: How does a beginning

filmmaker manage to get someone as legendary as John Sayles as a

producer?

|

| Writer-director John Sayles. |

BOB K: John had been a hero of

mine since I saw MATEWAN as a kid. That film taught me that

movies could have something to say and entertain at the same time.

His name stuck with me for years. When I ended up working in a video

store through college, I was able to watch all his movies, and just

admired the honesty of his characters, and the reality of the

situations he put them in.

Years later, around 2012, I was given

an opportunity to produce a film—almost any film I wanted—on a

respectable indie budget. A venture capital firm offered me the

chance, and I’d successfully produced before, and they thought I

had good taste and judgment. So this was a big opportunity. I

immediately reached out to John Sayles through his reps to see what

he might be interested in making for the kind of budget they were

proposing. He and I met, we talked, and we got along easily. We both

love old movies, and writing, and exploring ideas of who we are and

how we got here, so we had plenty to talk about.

BD: What was this film about?

BOB K: John wanted to make a

movie about Julius and Ethel Rosenberg—this historic 1950’s spy

trial, and the surrounding frenzy that ensued. It was an excellent

script. It was supported by the Rosenberg’s living children. It was

a very tense, human, even-handed look at he subject. It was, and

still is, a timely story. Coincidentally, I’d done a ton of

research on that subject for another project, and it was very

familiar to me.

|

| ''Doomed to die'', as was the film project by John Sayles about the infamous spy couple. Although it may resurface eventually. |

Ultimately, the head of the firm wanted John to admit that the Rosenberg’s were war criminals in what became a very confrontational, very one-sided conference phone call. The head of the firm wanted John to agree that the Rosenbergs got what was coming to them before we could make the film. John explained he was coming at this story from the middle—trying to find the truth in it—a journalistic approach. When John tried to explain that, the head of the firm got frustrated and continued his rant. I interjected, and stood up for John, and his integrity as a filmmaker, and I chastised the people on the call for being inappropriate and unstudied on the very project they were seeking to finance. I parted company with the firm about two hours later, and they’ve never made a movie since.

I’m a producer on my films to avoid

situations like this. I raised nearly a fourth of the budget for H&B.

I actually get in and work on the business side until smoke comes out

of my ears. I really wanted to do that for one of John’s movies,

and we wound up producing together on ELSIE HOOPER and H&B

instead. I still think about the Rosenberg project often. It was

really something. A story worth telling. And John has a real vision

for it. Maybe one day...

BD: That's certainly a film I

would love to see. How is it to work with him?

BOB K: I think John knew I’d

just burned a major bridge at the venture capital firm, and he

started looking out for me. I don’t know why exactly. I think he’s

just a good and decent person, and he knew I needed some guidance and

direction, and he had my back from then on. He produced my short film

ELSIE HOOPER offering guidance and wisdom throughout. Over the

years, John has taught me a lot about writing, his film theory, story

structure, and discipline.

Eventually, John read H&B

and he wanted to see it made, as written, without compromise, and he

helped me see that through over several years of careful navigation

and council. At every turn of this production, he was there—giving

notes, offering advise, and guiding us through rocky waters. This

movie wouldn’t exist without him. And I probably wouldn’t have a

career. He’s one of my favorite people, and a supremely

intelligent, decent human being. I owe him a lot.

BD: You

also have been working a lot with writer-director Lucky McKee.

BOB K: My close friend and

producing partner Lucky McKee has been with this project for eight

years. We met when I co-produced THE WOMAN for him in

Massachusetts in 2010. He’s stayed with my wife and I for a couple

long summers while we’ve worked on various projects—including a

summer back in 2015 where we really started cooking on H&B.

Lucky was instrumental in navigating this path, sharing his wisdom,

and helping me learn storytelling and direction in a totally open,

transparent way. Lucky believes in helping the next guy over the

wall. He’s supremely generous, and knowledgeable, and a

staggeringly talented director. He’s also an excellent puppeteer, a

natural actor, an accomplished author, and one of my best friends.

|

| Puppeteer Lucky McKee peeks up from his post beneath the frame, on the set of ELSIE HOOPER. Copyright 2018 - Robert D. Krzykowski |

Above all, Lucky cares about people.

And it’s infectious. There’s a communal spirit to him and his

work. It’s rare. Lucky and I compete with one another for the

biggest movie collection. We’ve had some Black Friday blowouts

together. I think he’s still got me beat by a hundred or so. I’ll

have to ask the current count. Has to be well over a thousand movies

apiece now. Maybe two thousand at this point. I’m afraid to count.

Lucky makes the best film

recommendations of anyone I know. Wanna watch a good movie tonight?

Go on Twitter, give Lucky an idea of what you’re looking for, and

he’ll steer you to something amazing that you’ve never seen

before—or didn’t know you wanted to see. Hit him up for your next

movie night. Tell him Bob K. sent you! Haha.

BD: I

just might. You

managed to wrangle another legendary name in movie-making for H&B;

Douglas Trumbull.

BOB K: Douglas Trumbull’s

legacy as a filmmaker and effects wizard has been with me since I was

a kid. I’ve always enjoyed classic effects, and cloud tank

photography is a hobby of mine. I have hours of high speed tank

footage, and it’s all because of trying to emulate Doug’s

gorgeous practical effects work with water, controlled lights,

powders, and paints. My kitchen can look like ‘Breaking Bad’ when

I’m trying to create a new effect.

By chance, Doug invited a group of

Massachusetts filmmakers to his lovely studio in the Berkshires a few

years ago. As everyone left, I showed him an old HEAVY METAL

magazine that was from the month and year that my wife was born.

February, 1984. It said, “Douglas Trumbull’s Brainstorm” on the

cover. Inside was a big article about his latest film. I’d had this

magazine for years. Doug hadn’t seen it in forever and he signed it

for me, and was just incredibly pleasant and kind. And I figured I’d

never see him again.

A couple years later, I made the short film ELSIE HOOPER. The Massachusetts Film Office and the Berkshire Film Commission were very supportive of that little short, and they liked it a lot. Diane Pearlman at the Berkshire Film Commission sent the short to Doug, and I got a surprise email from Doug saying he’d like to meet. So we met. We talked a bunch about effects—old and new. He showed me his 3D MAGI high frame rate process—which is the best, most immersive 3D I’ve ever seen. And we began exploring how we might work together.

BD: It's surprising to see not

only his name associated with the film, but also another legend of

visual effects, Richard Yuricich.

BOB K: When H&B went

into production, Doug was one of the first to offer his services and

open his doors to our team. His ideas are so big, and so brilliant,

and he’s such a joyful, curious, searching person. I adore him. He

made the movie better at every turn. He knew the constraints on the

budget and found ways and methods to make these big ideas emerge on

the screen. All of our earliest conceptual meetings were done at

Trumbull Studios under his guidance and supervision, he became a

producer on the film, and he brought his good friend and legendary

effects genius Richard Yuricich on board to supervise all the effects

work in the film.

|

| FX wizards Douglas Trumbull and Richard Yuricich on one of the stages of Trumbull's own FX house; Entertainment Effects Group (EEG) in the eighties. |

BD: What

was Richard Yuricich's involvement in the film?

BOB K: Richard Yuricich and I

had so much fun coming up with all these wild ideas and old school

solutions for them. Richard loves problem solving. He is undeterred

in the face of the biggest challenge. He cuts right to the best

methods and spends real time making sure his idea is understood and

can be implemented in an elegant way. Miniatures, matte paintings,

whatever trick we could use. There’s a lot of subtle modern effects

work in the film as well. All at the service of the story. Richard

was always pushing for the least amount of effects that could serve

the most immediate elements of the story. So we were judicious and

tactical. There’s nothing terribly flamboyant about the effects

work here. Which makes all these legends being a part of it all the

more unique. Their work is nearly invisible. But it’s everywhere.

Richard has a twinkle in his eye, he loves film, he’s a true

storyteller, and he’s such a happy person—up for any challenge.

We worked closely together and it was some of my happiest memories on

the film.

BD: You do have an impressive

visual effects team for a film that wasn't at first glance a showcase

for special effects. I see in the credits you also had Rocco

Gioffre, another legend in the field.

BOB K: Richard brought on Rocco

Gioffre, one of the greatest matte painters and effects artists of

all time. And Rocco is actually in the movie as the Nazi at the desk

checking in all of Young Barr’s personal belongings. So I suppose

Rocco is partially responsible for Hitler’s death, having let this

makeshift gun slip past him. I don’t think Rocco had ever acted

before, but he’s a lovely person, and he has a killer look, and it

just kept occurring to me—he should be in this film. He’s so good

in those opening moments. He sets the tone and energy of the film.

And then he’s behind-the-scenes doing the very same thing as an

effects wizard in a bunch of shots that he did himself or supervised

when he was on set every day. Rocco is in the bloodstream of this

film. That’s such a wonderful realization. So. All of a sudden I

looked around—and I was surrounded by my heroes. It’s all totally

unbelievable. I’ve looked up to these guys my whole life, and

suddenly I’m creating a movie with them.

|

| Matte Painting legend Rocco Gioffre working om CLIFFHANGER (1993) |

BD: Speaking of special effects,

the costume work on the Bigfoot is particularly impressive...and also

different than the usual depictions of the creature.

BOB K: Spectral Motion came on

board led by Mike Elizalde and his wonderful team. They created this

old-fashioned movie monster with The Bigfoot. We wanted to go way

back to the Universal Monsters. Man in a suit. Great makeup. Very

classic. Totally captured the tortured Bernie Wrightson spirit we were

going for. There’s even a touch of the 2001 apes in there. Yet,

it’s not a Bigfoot you’ve seen before. It’s smaller, stranger,

more emaciated. It has these haunted, Gollum-like eyes. Just one more

of the little surprises we tried to bring to the movie—keeping a

lot of these elements honest somehow, but just left-of-center.

With this entire team, sometimes

wonderful things just happen and you don’t question why. You just

keep marching forward and hoping to stay on course. You seek out

like-minded people. Or maybe they seek you? Again, it’s all

mysterious in some way. I couldn’t have been in better company

here. It was really special.

|

| Mike Elizalde touching up Ron Perlman's makeup on HELLBOY (2004) |

BD: Sam Elliott is amazing as Calvin Barr. Was he your only choice for the role?

BOB K: Sam was one of the

earliest choices, and certainly the one that meant the most to me

personally. When Sam said yes, I really started to believe this thing

could work. He exemplifies so many of the things we were trying to

shine a light on here, and he embodies that classic, Norman

Rockwell-esque heroism. He’s iconic in his own right, and so that

energy is transferred to the character he’s playing, and it’s a

thing to behold—in the making of the film, and with an audience.

|

| A hero right out of a Norman Rockwell illustration. Sam Elliott as Calvin Barr in THE MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN THE BIGFOOT.. |

BD: What do you feel he brought to the role?

BOB K: Sam brought a depth of

seriousness to the entire project. He told me he wanted to find the

reality here, and he had something he wanted to say about how we

treat one another today. And that was certainly something I was

striving for as well. So we were unified in our hopes for this thing.

And we talked a lot. We collaborated openly. There are so many

moments where Sam’s humanity is revealed through this character,

and he gives the audience something of his soul—and something that

should seem preposterous or surreal becomes moving and meaningful.

BD: He

does bring a lot of humanity and pathos to a character that could

have easily been a caricature in the hands of a lesser actor.

BOB K: Sam understood and

embraced the parable-like elements of the story, and the magical

realism at play, and he was careful never to tip it into something

exploitive or silly. He met some of the most bizarre elements

head-on, and I was able to watch the crew as he delivered these

scenes one after another. People were visibly moved. He could give

you chills. Ron Livingston’s off-screen reactions to Sam’s speech

about Nazism and the plague-like notion of ideas was something I’ll

never forget. This is a very strange story to balance, and we were

walking on a razor’s edge, and Sam is the reason this film has a

sense of realism and honesty—because that’s what Sam embodies as

a person. He’s honest. There aren’t many actors that could

balance what he’s doing here. It’s a thing to reckon with. He’s

heartbreaking and magnificent in this film. I can never repay him for

wishing to be a part of it. It meant the world.

BD: Was the pulpish title

helpful in getting attention from talent and investors, or was it

making things more complicated?

BOB K: No one ever suggested a

better title, so it just stood. Changing it to something more

ambiguous or simplistic felt sneaky somehow. Either way, the audience

would discover this totally strange thing waiting for them. The title

felt like the most honest, straightforward way to describe what

people were getting themselves into, and let them decide if they

would embark or not. I also felt the title hinted there must be

something more here since it kinda gives the whole movie away.

But yes—the title got people’s

attention. They usually wanted to know more. I had a lot of

conceptual designs and storyboards to reveal some of the vision, and

that helped a lot to let people know there was more going on than

just a shocking title. If someone read the script, that was always

the dividing line. One out of twenty people would want to be a part

of it. That one out of twenty was always someone really, really

special. Sometimes they’d be one of my all-time heroes. And that

told me this was a story worth telling.

BD: How did the World Premiere

go, at the Montreal Fantasia Film Festival? I could tell you were

very nervous.

|

| Robert Krzykowski during the Q&A session after the World Premiere of THE MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN THE BIGFOOT at The Montreal Fantasia Film Festival. (Photo by Julie Delisle) |

BOB K: I was nervous. I don’t enjoy being in front of lots of people, and I’m not always eloquent on the fly. That said, the audience was so alive, boisterous, and receptive. The Festival heads were lovely and supportive. When you write a script, you try to envision how it might interact with an audience. You try to track, predict, and surprise their emotional responses from page-to-page. At Fantasia, that audience was a dream version of those hopes. I know the creative team in that packed theater felt likewise. It was a special moment, being there. I won’t forget it.

|

| Sam Elliott facing a capacity crowd at the World Premiere of THE MAN WHO KILLED HITLER AND THEN THE BIGFOOT at the Montreal Fantasia Film Festival (Photo by Julie Delisle) |

BD: Congratulations on doing very well on Rotten Tomatoes. Looks like reviewers are praising, deservedly, the film. Is it already opening doors for future projects? What can we expect from you in the future?

BOB K: Thank you. If people are

finding this well, that makes me happy. It’s theirs now. I will

shortly fade into the role of a bystander. And I’m happy about

that. As a producer on the film, a lot of my business duties haven’t

completely ended yet. When the dust settles, I look forward to

getting home to Massachusetts and taking a moment to exhale. My

writing desk is waiting for me, and I’m excited to return to a bit

of normalcy, and figure it all out. For now, I’m grateful for the

chance to talk about the film with you, and I look forward to further

adventures—whatever that may be.

BD: Thank you so much for your time and generosity in this interview, and looking forward to your next project.

BD: Thank you so much for your time and generosity in this interview, and looking forward to your next project.

|

| Sam Elliott

during the Q&A session after the World Premiere of THE MAN WHO

KILLED HITLER AND THEN THE BIGFOOT at The Montreal Fantasia Film

Festival. (Photo by Julie Delisle)

|

The movie game with SAM ELLIOTT

At the start of our interview in Fantasia's Green Room, I took a few minutes to quizz Sam Elliott on some of his films, asking him for the fist thing that came to his mind when I say the title of one of his many films. A silly exercise made by someone who was unprepared, but he played along.

BRAIN DEAD:

BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID.

SE:

My wife, Katherine.

BD:

Yes. But you didn’t meet her on that film, did you?

SE:

No I didn’t. I was a contract player at Fox when I made the film. I

had one line in the scene I was in, I was a shadow on the wall. Then

I met Katherine ten years later as we starred in a film in a couple

of scenes together.

BD:

EVEL KNIEVEL.

SE:

Lucky. I was lucky that it didn’t sell. It was a pilot for a show.

It ended up being, you know…But I did get to meet Evel Knievel,

which was a trip.

BD:

He was an amazing character.

SE:

He is. He was.

BD:

Of course: ROAD HOUSE.

SE:

Patrick Swayze. That’s the first thing that comes to mind.

BD:

How was it working on that film?

SE:

It was fun. You know that film was like the ultimate male fantasy.

(Laughter) I think more guys talk about that movie than anything I

have ever done. That and TOMBSTONE. It was a lot of fun but also a

lot of work, you know. The fights were a lot of work. We had a

two-time World Champion kickboxer, Billy The Jet, who trained us and

worked with us every day while we were in production. Did a lot of

fighting. I remember the biggest fight was on the last day of the

shoot for me. I remember the next morning barely being able to open

my eyes. I was not ready to move anywhere. It was …painful. I

wasn’t full on fighting, but we were taking body blows and that

kind of stuff, there was no way to avoid it when you’re doing those

kind of fights. A lot of work, but a lot of fun.

BD:

HULK.

SE:

Ang Lee. The good fortune to be able to work with Ang Lee.

BD:

Too bad they didn’t stay with you when they did…(replace him with

William Hurt in the follow-up THE INCREDIBLE HULK)

SE:

They didn’t. But the movie wasn’t as successful as the first,

so…Don’t mess with it. And they didn’t have Ang Lee the second

time either.

BD:

GHOST RIDER.

SE:

Wow. Australia. We got to shoot down in Australia. You know it was a

lot of fun. It was very much like the kind of film we’re here to

promote.

|

| The author, hoping in vain his facial hair can one day be as legendary as Sam Elliott's. (Photo by King Wei Chu) |

Comments

Post a Comment